Prologue

This is second part of the rgbCTF writeup, and contains information about challenges solved by me, Emzi. I strongly suggest starting with the first part of this writeup.

This was my first CTF event, however not the first set of challenges I solved. As I’m new, the methods outlined here might seem somewhat unsophisticated, since I am not used to working on this side of the barricade.

I took part thanks to Still, who asked me to co-participate in this event at the last minute. I was hesitant at first, but decided it might be an educational experience. Through solving the challenges, I learned something new, and in some cases, jogged my memory.

Since categories and structure were outlined in the previous post, I will only focus on the challenges I solved, as well as the methods used to reach the solution.

Beginner

A Basic Challenge (50 points)

Challenge description

This is a nice and basic challenge.

Attached was a file called basic_chall.txt with the following contents:

110100 1100100 100000 110101 110100 100000 110101 111001 100000 110111 111001 100000 110100 111001 100000 110100 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110011 110000 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110111 111001 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 111000 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110100 110100 100000 110100 111001 100000 110110 110111 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110101 110100 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 1100001 100000 110100 111001 100000 110100 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110111 111001 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110100 110011 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 111000 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110100 110100 100000 110101 111001 100000 110110 110111 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110101 110100 100000 110110 110011 100000 110111 1100001 100000 110100 111001 100000 110100 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110011 110000 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110111 111001 100000 110100 110001 100000 110011 110010 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110100 110011 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 111000 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110101 110100 100000 110101 111001 100000 110110 110111 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110101 110100 100000 110101 110001 100000 110011 110011 100000 110100 111001 100000 110100 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110011 110010 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110110 111001 100000 110100 110001 100000 110011 110010 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110100 110011 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 111000 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110110 1100001 100000 110101 110001 100000 110110 110111 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110101 110100 100000 110101 111001 100000 110111 1100001 100000 110100 111001 100000 110100 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110111 1100001 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110111 111001 100000 110100 110001 100000 110011 110010 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110100 110011 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 111000 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110101 110100 100000 110101 111001 100000 110110 110111 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110101 110100 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110011 110011 100000 110100 111001 100000 110100 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110011 110000 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110110 111001 100000 110100 110001 100000 110011 110010 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110111 111001 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 111000 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110101 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110110 110111 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110101 110100 100000 110101 110101 100000 110011 110010 100000 110100 111001 100000 110100 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110011 110000 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110111 111001 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 111000 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110111 1100001 100000 110110 110011 100000 110110 110111 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110101 110100 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 111001 100000 110100 111001 100000 110100 110100 100000 110101 111001 100000 110011 110000 100000 110100 111001 100000 110100 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110111 111001 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110111 111001 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 111000 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110101 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110110 110111 100000 110100 1100100 100000 110101 110100 100000 110100 110001 100000 110111 1100001 100000 110100 111001 100000 110100 110100 100000 110100 110101 100000 110011 110011 100000 110100 1100101 100000 110101 110001 100000 110011 1100100 100000 110011 1100100

This challenge proved to be a case of not using something for so long you even forget it exists, and you will soon find out why. But let’s get going. The string in front of me is very obviously a binary-encoded string, meaning that since it’s in the Beginner category, it’s a classic multilayer decoding challenge. I think most people reading this played with various encoding tools when they were younger, so this looks like a very straightforward challenge. I fired up the python REPL and got to work. This challenge is also solvable entirely using online tools, but I figured it’s more fun this way.

I started off by loading the file and parsing the binary.

with open("basic_chall.txt", "r") as f:

t = f.read()

t2 = [int(x, 2) for x in t.split(' ')]

t2

The result was this:

[52, 100, 32, 53, 52, 32, 53, 57, 32, 55, 57, 32, 52, 57, 32, 52, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 51, 48, 32, 52, 101, 32, 55, 57, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 56, 32, 52, 101, 32, 52, 52, 32, 52, 57, 32, 54, 55, 32, 52, 100, 32, 53, 52, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 97, 32, 52, 57, 32, 52, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 55, 57, 32, 52, 101, 32, 52, 51, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 56, 32, 52, 100, 32, 52, 52, 32, 53, 57, 32, 54, 55, 32, 52, 100, 32, 53, 52, 32, 54, 51, 32, 55, 97, 32, 52, 57, 32, 52, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 51, 48, 32, 52, 100, 32, 55, 57, 32, 52, 49, 32, 51, 50, 32, 52, 100, 32, 52, 51, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 56, 32, 52, 101, 32, 53, 52, 32, 53, 57, 32, 54, 55, 32, 52, 100, 32, 53, 52, 32, 53, 49, 32, 51, 51, 32, 52, 57, 32, 52, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 51, 50, 32, 52, 100, 32, 54, 57, 32, 52, 49, 32, 51, 50, 32, 52, 101, 32, 52, 51, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 56, 32, 52, 101, 32, 54, 97, 32, 53, 49, 32, 54, 55, 32, 52, 100, 32, 53, 52, 32, 53, 57, 32, 55, 97, 32, 52, 57, 32, 52, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 55, 97, 32, 52, 101, 32, 55, 57, 32, 52, 49, 32, 51, 50, 32, 52, 100, 32, 52, 51, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 56, 32, 52, 101, 32, 53, 52, 32, 53, 57, 32, 54, 55, 32, 52, 100, 32, 53, 52, 32, 52, 100, 32, 51, 51, 32, 52, 57, 32, 52, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 51, 48, 32, 52, 100, 32, 54, 57, 32, 52, 49, 32, 51, 50, 32, 52, 100, 32, 55, 57, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 56, 32, 52, 101, 32, 53, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 54, 55, 32, 52, 100, 32, 53, 52, 32, 53, 53, 32, 51, 50, 32, 52, 57, 32, 52, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 51, 48, 32, 52, 101, 32, 55, 57, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 56, 32, 52, 100, 32, 55, 97, 32, 54, 51, 32, 54, 55, 32, 52, 100, 32, 53, 52, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 57, 32, 52, 57, 32, 52, 52, 32, 53, 57, 32, 51, 48, 32, 52, 57, 32, 52, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 55, 57, 32, 52, 100, 32, 55, 57, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 56, 32, 52, 100, 32, 53, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 54, 55, 32, 52, 100, 32, 53, 52, 32, 52, 49, 32, 55, 97, 32, 52, 57, 32, 52, 52, 32, 52, 53, 32, 51, 51, 32, 52, 101, 32, 53, 49, 32, 51, 100, 32, 51, 100]

That’s a decimal integer array, where all integers were in range 0 ≤ x ≤ 255. Seems like plain ASCII characters to me, so I modified above snippet slightly to get a string.

t2 = ''.join(chr(int(x, 2)) for x in t.split(' '))

t2

This time, the output looked like this:

'4d 54 59 79 49 44 45 30 4e 79 41 78 4e 44 49 67 4d 54 41 7a 49 44 45 79 4e 43 41 78 4d 44 59 67 4d 54 63 7a 49 44 45 30 4d 79 41 32 4d 43 41 78 4e 54 59 67 4d 54 51 33 49 44 45 32 4d 69 41 32 4e 43 41 78 4e 6a 51 67 4d 54 59 7a 49 44 45 7a 4e 79 41 32 4d 43 41 78 4e 54 59 67 4d 54 4d 33 49 44 45 30 4d 69 41 32 4d 79 41 78 4e 54 45 67 4d 54 55 32 49 44 45 30 4e 79 41 78 4d 7a 63 67 4d 54 41 79 49 44 59 30 49 44 45 79 4d 79 41 78 4d 54 45 67 4d 54 41 7a 49 44 45 33 4e 51 3d 3d'

That’s a hexadecimal string. So we’re past first layer - base2. On to decoding this one.

t3 = [int(x, 16) for x in t2.split(' ')]

t3

The result is, again, an integer array:

[77, 84, 89, 121, 73, 68, 69, 48, 78, 121, 65, 120, 78, 68, 73, 103, 77, 84, 65, 122, 73, 68, 69, 121, 78, 67, 65, 120, 77, 68, 89, 103, 77, 84, 99, 122, 73, 68, 69, 48, 77, 121, 65, 50, 77, 67, 65, 120, 78, 84, 89, 103, 77, 84, 81, 51, 73, 68, 69, 50, 77, 105, 65, 50, 78, 67, 65, 120, 78, 106, 81, 103, 77, 84, 89, 122, 73, 68, 69, 122, 78, 121, 65, 50, 77, 67, 65, 120, 78, 84, 89, 103, 77, 84, 77, 51, 73, 68, 69, 48, 77, 105, 65, 50, 77, 121, 65, 120, 78, 84, 69, 103, 77, 84, 85, 50, 73, 68, 69, 48, 78, 121, 65, 120, 77, 122, 99, 103, 77, 84, 65, 121, 73, 68, 89, 48, 73, 68, 69, 121, 77, 121, 65, 120, 77, 84, 69, 103, 77, 84, 65, 122, 73, 68, 69, 51, 78, 81, 61, 61]

Let’s modify the snippet again.

t3 = ''.join(chr(int(x, 16)) for x in t2.split(' '))

t3

And as an output, we get a base64 string. So we’re past second layer - base16:

'MTYyIDE0NyAxNDIgMTAzIDEyNCAxMDYgMTczIDE0MyA2MCAxNTYgMTQ3IDE2MiA2NCAxNjQgMTYzIDEzNyA2MCAxNTYgMTM3IDE0MiA2MyAxNTEgMTU2IDE0NyAxMzcgMTAyIDY0IDEyMyAxMTEgMTAzIDE3NQ=='

So far so good, let’s decode it.

from base64 import b64decode

b64decode(t3)

After stripping the 3rd layer - base64 - we get an output which is a string of integers:

b'162 147 142 103 124 106 173 143 60 156 147 162 64 164 163 137 60 156 137 142 63 151 156 147 137 102 64 123 111 103 175'

However, this time something about them is off, can you see it? Most of these values, if treated as decimal, then converted to characters, would produce unprintable characters, or otherwise garbled text. I tried it regardless.

''.join(chr(int(x)) for x in b64decode(t3).decode().split(' '))

And the output was, predictably, useless:

'¢\x93\x8eg|j\xad\x8f<\x9c\x93¢@¤£\x89<\x9c\x89\x8e?\x97\x9c\x93\x89f@{og¯'

I decided to look through all sorts of common text encoding schemes, as well as experiment with shifting or XORing the values, but to no avail. Eventually, one of my friends noticed that the values look surprisingly like octal (base8) numbers. So let’s try it.

''.join(chr(int(x, 8)) for x in b64decode(t3).decode().split(' '))

And indeed, after stripping the 4th layer of encoding, we get our flag as the output:

'rgbCTF{c0ngr4ts_0n_b3ing_B4SIC}'

The irony in this is that octal is an encoding a lot of UNIX people use frequently without realizing it (chmod permission flags are octal, for instance), yet it never occurred to me that it could be something as simple and trivial as this.

Flag:

rgbCTF{c0ngr4ts_0n_b3ing_B4SIC}

Pieces (50 points)

Challenge description

My flag has been divided into pieces :( Can you recover it for me?

Attached was a file called Main.java with the following contents:

import java.io.*;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

BufferedReader in = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(System.in));

String input = in.readLine();

if (divide(input).equals("9|2/9/:|4/7|8|4/2/1/2/9/")) {

System.out.println("Congratulations! Flag: rgbCTF{" + input + "}");

} else {

System.out.println("Incorrect, try again.");

}

}

public static String divide(String text) {

String ans = "";

for (int i = 0; i < text.length(); i++) {

ans += (char)(text.charAt(i) / 2);

ans += text.charAt(i) % 2 == 0 ? "|" : "/";

}

return ans;

}

}

Analysis of the code reveals that the flag contents have been encoded. The process took every character, halved its ASCII value, and wrote the resulting character out, then appdended either | or /, depending on whether the character’s value was divisible by 2 or not. In effect, each character was encoded as a pair of (div 2, mod 2).

Reversing this process was simple, and I decided to use C# to achieve this. My program simply took each character pair, multiplied the ASCII value of the first character of each pair by 2, then added 1 if the other character was equal to /. The source code of the entrypoint of the program can be found below.

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

var str = "9|2/9/:|4/7|8|4/2/1/2/9/";

var sts = str.AsSpan();

for (int i = 0; i < str.Length; i += 2)

{

var addone = sts[i + 1] == '/';

var ch = (char)((sts[i] * 2) + (addone ? 1 : 0));

Console.Write(ch);

}

Console.WriteLine();

}

When ran, the program spit out the string restinpieces.

Flag:

rgbCTF{restinpieces}

r/ciphers (50 points)

Challenge description

RGBsec does not endorse (or really even know at this point) what the content is on that sub reddit. (It's just the title of the challenge)

Attached was a file called 11.txt with the following contents:

Nfwp wp z hkakzudfzoinwj plopnwnlnwka jwdfix, yfwjf jza oi znnzjgit ywnf mxicliajs zazuspwp. Zunfklqf nfwp znnzjg jza oi tkai os fzat, wn'p lplzuus hljf izpwix nk lpi z dxkqxzh nk tk wn mkx skl. Nyk qkkt yiopwnip nfzn ywuu tijxsdn plopnwnlnwka jwdfixp mkx skl zxi zn qlozuuz.ti/plopnwnlnwka-pkuvix zat clwdcwld.jkh. Wm skl fzvia'n nxwit nfih oimkxi, skl pfklut jfijg nfih kln. Fixi'p sklx muzq: xqoJNM{blpn_4pg_nf3_wan3xa3n_n0_t3jxsdn_wn}

Zupk, Zuij oiuwivip wn'p vixs whdkxnzan nfzn skl pii nfwp: fnndp://w.xitt.wn/1d7y8g0272851.bdq

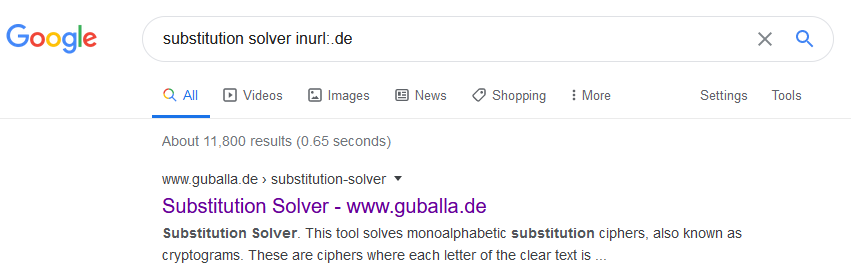

The challenge looked like a simple substitution cipher challenge, so my first thought was to find patterns, perform some frequency analysis, then get cracking.

One thing I noticed right off the bat is that only letters were substituted, digits and other characters were left alone. Since the title of the challenge is reddit-related, so the first thing that stood out to me, was this: fnndp://w.xitt.wn/1d7y8g0272851.bdq. It’s obviously an i.redd.it link, which makes .bdq its extension. It’s an image, so it’s either .gif, .png, or .jpg. Another part of the URL, fnndp:// was clearly https://, meaning that combined with knowing the domain, we now have some letters for the alphabet:

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz original

ti fw d xpn substituted

Looking at this, we notice that d maps to p, so bdq is _p_. Of the 3 suspect extensions, jpg is the only match, so we now add 2 more letters:

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz original

ti qfwb d xpn substituted

Next piece of interest is the flag: xqoJNM{blpn_4pg_nf3_wan3xa3n_n0_t3jxsdn_wn}. We know it’s in the standard format (rgbCTF{flag}), so we can map more letters. As this looks like a simple substitution cipher, I assumed that different case of the same letter maps the same, and thus we add the following to our alphabet:

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz original

ojtimqfwb d xpn substituted

At this stage, we can perform partial reconstruction of the flag: rgbCTF{j st_4s _th3_i t3r 3t_t0_d3cr pt_it}. Obvious standout here is the second to last word of the flag, d3cr pt, as well as the first, j st. With these 2, we can deduce 2 more letters:

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz original

ojtimqfwb d xpnl s substituted

There are 2 more domains in the text: qlozuuz.ti/plopnwnlnwka-pkuvix and clwdcwld.jkh. Decoding the first one yields gub .de/substituti -s er, while the second one yields uip uip.c. My guess is that it’s a .com domain, so I added the 2 letters to the map:

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz original

ojtimqfwb h kd xpnl s substituted

And with that, the path of the first domain got updated to /substitutio -so er. Given what this challenge is, I filled in the blanks to make it /substitution-solver, mapping 3 more letters in the process:

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz original

ojtimqfwb uhakd xpnlv s substituted

So let’s reconstruct what we’ve got of the flag: rgbCTF{just_4s _th3_int3rn3t_t0_d3crypt_it}. It looked like Just ask the internet to decrypt it, so I mapped k.

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz original

ojtimqfwbguhakd xpnlv s substituted

At this stage, we have the flag, rgbCTF{just_4sk_th3_int3rn3t_t0_d3crypt_it}, but I decided to finish decoding the first domain: gub ll .de/substitution-solver. A quick google search led me right to the rest of the result, guballa.de:

At this stage, our alphabet looks like this:

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz original

zojtimqfwbguhakd xpnlv s substituted

Just to confirm my work, I punched the entire text into the solver, and the result matched:

As a bonus, the i.redd.it link in the text led to this image:

Flag:

rgbCTF{just_4sk_th3_int3rn3t_t0_d3crypt_it}

Cryptography

Occasionally Tested Protocol (219 points)

Challenge description

But clearly not tested enough... can you get the flag?

We were also given an address to connect to using netcat, and attached was a python script, called otp.py, with the following contents:

from random import seed, randint as w

from time import time

j = int

u = j.to_bytes

s = 73

t = 479105856333166071017569

_ = 1952540788

s = 7696249

o = 6648417

m = 29113321535923570

e = 199504783476

_ = 7827278

r = 435778514803

a = 6645876

n = 157708668092092650711139

d = 2191175

o = 2191175

m = 7956567

_ = 6648417

m = 7696249

e = 465675318387

s = 4568741745925383538

s = 2191175

a = 1936287828

g = 1953393000

e = 29545

g = b"rgbCTF{REDACTED}"

if __name__ == "__main__":

seed(int(time()))

print(f"Here's 10 numbers for you: ")

for _ in range(10):

print(w(5, 10000))

b = bytearray([w(0, 255) for _ in range(40)])

n = int.from_bytes(bytearray([l ^ p for l, p in zip(g, b)]), 'little')

print("Here's another number I found: ", n)

The script turned out to be abridged version of the code running at the specified endpoint. The variables (with the exception of g) looked rather unimportant, so for local testing, one could’ve simply removed them all. Cursory analysis of the algorithm also reveals the challenge type - PRNG state reversing, with seed(int(time)) being the key to the whole thing.

A little bit of background - Python’s time.time() function returns the current UNIX timestamp as fractional seconds, e.g. 1594735323.0495105. Had the RNG been seeded using the entire number, this would’ve been a very tedious challenge indeed, as it would require going through a large number of fractions to find the proper seed. Lucky for us, the seed was converted into an integer using int(). When the input to int() is a floating-point number, it works much like casting in C - the number is truncated to whole part (as an example, int(1594735323.0495105) results in 1594735323; note that no rounding is performed - int(1.9) results in 1).

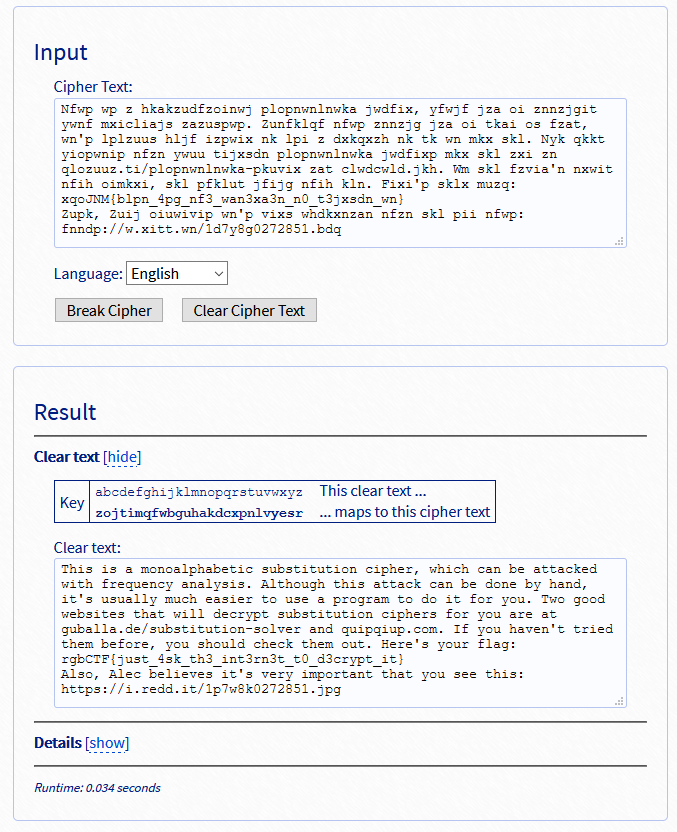

Armed with that knowledge, I performed a timestamped netcat connection via date +%s; nc endpoint port, then disconnected once I got my numbers. Worth noting: most values below are examples rather than exact values used, as the writeup was made after the challenge deadline closed.

The timestamp is the first line (duh), so the data required to reverse the state was as follows:

cseed = 1594735574

nums = [7324, 3820, 9253, 4368, 8756, 2211, 1602, 722, 2226, 4959]

flagnum = 7424730967707779449792579718502356899503369464409389298411900681059

With this, I could start my search for the seed. I whipped up a script and set it loose.

from random import seed, randint

cseed = 1594735574

nums = [7324, 3820, 9253, 4368, 8756, 2211, 1602, 722, 2226, 4959]

while True:

seed(cseed)

t = [randint(5, 10000) for x in range(10)]

if t == nums:

print("Seed found:", cseed)

print("Sequence:", t)

break

cseed += 1

It looks scary and has the potential to iterate indefinitely, but the output of date was at most a couple seconds away from receiving the input from server, so this would only ever run at a couple iterations at most. At any rate, in this instance, computed seed was 1594735575.

That’s first part of the challenge completed, I now needed to figure out the flag. In order to obtain the flag string, I analyzed these 2 lines:

b = bytearray([w(0, 255) for _ in range(40)])

n = int.from_bytes(bytearray([l ^ p for l, p in zip(g, b)]), 'little')

In the above, g is the flag string. What occurs here, is that 40 random bytes are generated (after the initial 10 values), and then zipped with the flag string g variable. Elements of the tuples produced by zip are then XORed together, and resulting bytes are encoded into a huge integer value.

XOR (^ in python) is an interesting operator. It is associative ((a ^ b) ^ c = a ^ (b ^ c) for every a, b, and c), commutative (a ^ b = b ^ a for every a and b), has an identity element of 0 (a ^ 0 = a for every a), is self-inversible (a ^ a = 0 for every a), but most importantly, for any given a, b, and c, performing a ^ b = c, you can get the value of a if you have b by performing a = c ^ b, and similarly for b, given value of a, via b = c ^ a. That last property is why it’s commonly-used in cryptography.

That last bit is the key to retrieving the flag for the CTF. In this instance, I’m given a collection of bytes corresponding to c and b from above explanation, and I’m looking for a. The large number contains my c bytes, the random sequence is my b bytes. Flag is the a bytes.

In order to retrieve the flag, I have to generate 10 numbers 5-10000, then 40 bytes, using the seed I computed. Next up, I have to decode the big integer into bytes. Obtaining the flag is trivial afterwards. So I whipped up another script.

from random import seed, randint

cseed = 1594735575

flagnum = 7424730967707779449792579718502356899503369464409389298411900681059

flaglen = (flagnum.bit_length() + 7) // 8 # number of bytes the flag has - in this instance 28

seed(cseed)

[randint(5, 10000) for x in range(10)] # generate the 10 numbers first

b = bytes(randint(0, 255) for _ in range(flaglen)) # don't need more bytes

c = flagnum.to_bytes(flaglen, 'little')

a = ''.join(chr(x ^ y) for x, y in zip(b, c))

print(a)

That script produced the flag string, which means the challenge is completed.

Flag:

rgbCTF{random_is_not_secure}

N-AES (473 points)

Challenge description

What if I encrypt something with AES multiple times?

We were also given an address to connect to using netcat, and attached was a python script, called n_aes.py, with the following contents:

import binascii

from base64 import b64encode, b64decode

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad, unpad

from os import urandom

from random import seed, randint

BLOCK_SIZE = 16

def rand_block(key_seed=urandom(1)):

seed(key_seed)

return bytes([randint(0, 255) for _ in range(BLOCK_SIZE)])

def encrypt(plaintext, seed_bytes):

ciphertext = pad(b64decode(plaintext), BLOCK_SIZE)

seed_bytes = b64decode(seed_bytes)

assert len(seed_bytes) >= 8

for seed in seed_bytes:

ciphertext = AES.new(rand_block(seed), AES.MODE_ECB).encrypt(ciphertext)

return b64encode(ciphertext)

def decrypt(ciphertext, seed_bytes):

plaintext = b64decode(ciphertext)

seed_bytes = b64decode(seed_bytes)

for byte in reversed(seed_bytes):

plaintext = AES.new(rand_block(byte), AES.MODE_ECB).decrypt(plaintext)

return b64encode(unpad(plaintext, BLOCK_SIZE))

def gen_chall(text):

text = pad(text, BLOCK_SIZE)

for i in range(128):

text = AES.new(rand_block(), AES.MODE_ECB).encrypt(text)

return b64encode(text)

def main():

challenge = b64encode(urandom(64))

print(gen_chall(challenge).decode())

while True:

print("[1] Encrypt")

print("[2] Decrypt")

print("[3] Solve challenge")

print("[4] Give up")

command = input("> ")

try:

if command == '1':

text = input("Enter text to encrypt, in base64: ")

seed_bytes = input("Enter key, in base64: ")

print(encrypt(text, seed_bytes))

elif command == '2':

text = input("Enter text to decrypt, in base64: ")

seed_bytes = input("Enter key, in base64: ")

print(decrypt(text, seed_bytes))

elif command == '3':

answer = input("Enter the decrypted challenge, in base64: ")

if b64decode(answer) == challenge:

print("Correct!")

print("Here's your flag:")

with open("flag", 'r') as f:

print(f.read())

else:

print("Incorrect!")

break

elif command == '4':

break

else:

print("Invalid command!")

except binascii.Error:

print("Base64 error!")

except Exception:

print("Error!")

print("Bye!")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

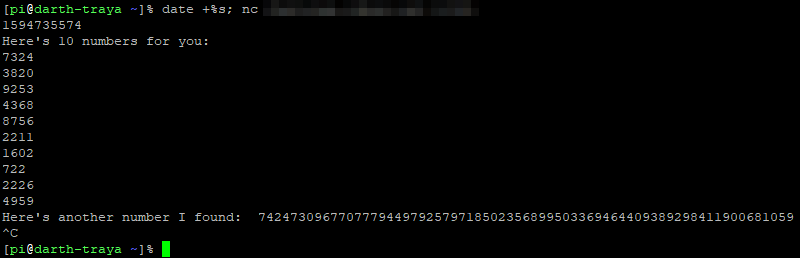

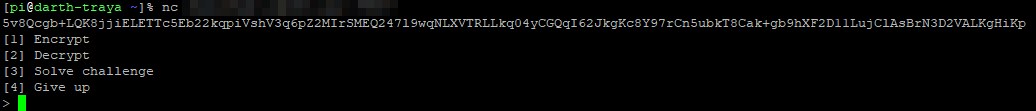

Much like with the previous challenge, attached script is the abridged source of the program at the given endpoint. Unlike the previous one, however, it appeared to be a codebreaking challenge. Looks can be deceiving however, and so it was in this instance. Again: most values below are examples rather than exact values used, as the writeup was made after the challenge deadline closed.

Upon connecting, the program greeted me with a base64 challenge string. I was a little confused as to where to start at first, so I decided to analyze the source again. Tracing the challenge string generation code revealed interesting things, however, and something I overlooked at first.

The final challenge solve text is also a base64 string, which has been encrypted. My job was to decrypt it, that is, to find the key used to encrypt it. Scanning the imports revealed the encryption to be AES, with PCKS#7 padding.

The padding bit is important, as it lets you determine whether your process was successful. This padding algorithm works by filling the last block of the input, such that its output size is aligned to desired block size. The filler bytes double as a padding size counter, meaning that if the block is missing e.g. 3 bytes, it will be filled with 3 '\x03' bytes. If the input is already at block size, PKCS#7 appends a new empty block, then fills it with padding.

Further analysis of the program reveals that the AES variant used here is 128-bit, so it uses 16-byte (128-bit) blocks. Looking at the challenge generation code, it generates 64 random bytes, which are then encoded with base64. Base64 emits a character (byte) for every 6 bits of input, meaning the output string is around 133% the size of input. In this case, the base64 string was 88 characters long. As 88 is not divisible by the block size (16), I had to find block-aligned input size that AES would accept. For 88 bytes, that 96 bytes, meaning PKCS#7 would append 8 bytes of padding - b'\x08' * 8. That’s my sentinel value, of sorts.

The challenge is then passed to the gen_chall function:

def gen_chall(text):

text = pad(text, BLOCK_SIZE)

for i in range(128):

text = AES.new(rand_block(), AES.MODE_ECB).encrypt(text)

return b64encode(text)

Here, the padding is appended, and the text is then encrypted 128 times, using key which is the output of rand_block(). The encryption output is then base64-encoded. The key generation function looks as follows:

def rand_block(key_seed=urandom(1)):

seed(key_seed)

return bytes([randint(0, 255) for _ in range(BLOCK_SIZE)])

Which initially seems rather hopeless, as at first glance it seems to generate a different key for every call with the default argument. But that is not, in fact, what happens. Function arguments in python are evaluated at the time of function creation, meaning they are computed exactly once. For this challenge, it means the challenge string is encrypted 128 times, each time with the same exact key. And since the function’s default argument is urandom(1), which produces 1 byte, there were exactly 256 possible keys. Great, now we’re getting somewhere.

However before I could proceed, I still had to analyze the remaining parts of the program. I decided to look at the encryption and decryption functions first.

def encrypt(plaintext, seed_bytes):

ciphertext = pad(b64decode(plaintext), BLOCK_SIZE)

seed_bytes = b64decode(seed_bytes)

assert len(seed_bytes) >= 8

for seed in seed_bytes:

ciphertext = AES.new(rand_block(seed), AES.MODE_ECB).encrypt(ciphertext)

return b64encode(ciphertext)

def decrypt(ciphertext, seed_bytes):

plaintext = b64decode(ciphertext)

seed_bytes = b64decode(seed_bytes)

for byte in reversed(seed_bytes):

plaintext = AES.new(rand_block(byte), AES.MODE_ECB).decrypt(plaintext)

return b64encode(unpad(plaintext, BLOCK_SIZE))

They aren’t conventional encryption and decryption functions, since they take a seed, which is a string of bytes, then perform their respective operation on the input byte string as many times, as there are bytes in the seed, using consecutive bytes from the seed to generate keys.

Looking at the entry point of the program, more specifically, the solve part, also reveals how the challenge is solved.

elif command == '3':

answer = input("Enter the decrypted challenge, in base64: ")

if b64decode(answer) == challenge:

print("Correct!")

print("Here's your flag:")

with open("flag", 'r') as f:

print(f.read())

else:

print("Incorrect!")

break

Decrypted challenge is decoded from base64, then compared to challenge string.

To summarize the story so far, my job was to:

- Generate 256 128-byte strings, each consisting of one byte

- Get the challenge string from the remote server

- Brute force it using generated keys

To achieve all that, I built a Python script, using parts of the challenge program.

from random import seed, randint

from base64 import b64encode, b64decode

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad, unpad

BLOCK_SIZE = 16

def rand_block(key_seed: bytes):

seed(key_seed)

return bytes([randint(0, 255) for _ in range(BLOCK_SIZE)])

def decrypt(input: bytes, key: bytes):

text = input

for _ in range(128):

text = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_ECB).decrypt(text)

return text, unpad(text, BLOCK_SIZE), b64encode(unpad(text, BLOCK_SIZE)).decode()

if __name__ == "__main__":

challenge = b64decode(input("Input challenge string: "))

print("-" * 32)

keys = [rand_block(bytes([x])) for x in range(256)]

for seed, key in enumerate(keys):

try:

t, u, b = decrypt(challenge, key)

if t[-8:] != (b'\x08' * 8):

continue

print("Decrypted: ", t)

print("Unpadded: ", u)

print("Encoded: ", b)

print("Seed: ", seed)

print("Key: ", b64encode(key).decode())

print("Seed string:", b64encode(bytes([seed] * 128)).decode())

print("-" * 32)

except:

continue

All that was left was connecting to the remote server to obtain my challenge string.

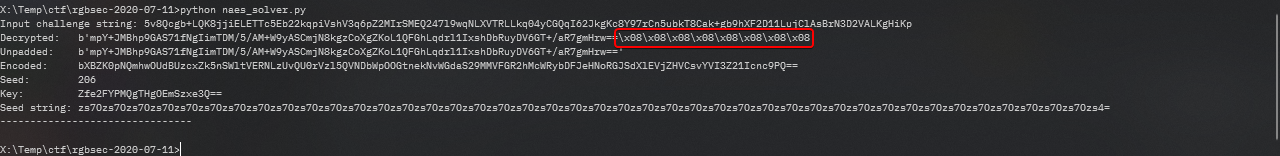

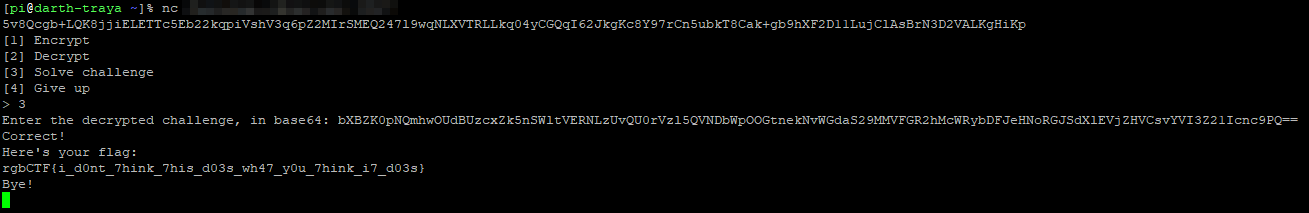

My challenge string in this instance is 5v8Qcgb+LQK8jjiELETTc5Eb22kqpiVshV3q6pZ2MIrSMEQ247l9wqNLXVTRLLkq04yCGQqI62JkgKc8Y97rCn5ubkT8Cak+gb9hXF2D11LujClAsBrN3D2VALKgHiKp. I punched it into my solver script, and got a solution. Highlighted in red is the aforementioned padding.

I punched the encoded result into netcat, and the server echoed me a flag.

Flag:

rgbCTF{i_d0nt_7hink_7his_d03s_wh47_y0u_7hink_i7_d03s}

Forensics/OSINT

PI 1: Magic in the air (470 points)

Challenge description

We are investigating an individual we believe is connected to a group smuggling drugs into the country and selling them on social media. You have been posted on a stake out in the apartment above theirs and with the help of space-age eavesdropping technology have managed to extract some data from their computer. What is the phone number of the suspect's criminal contact? flag format includes country code so it should be in the format: rgbCTF{+00000000000}

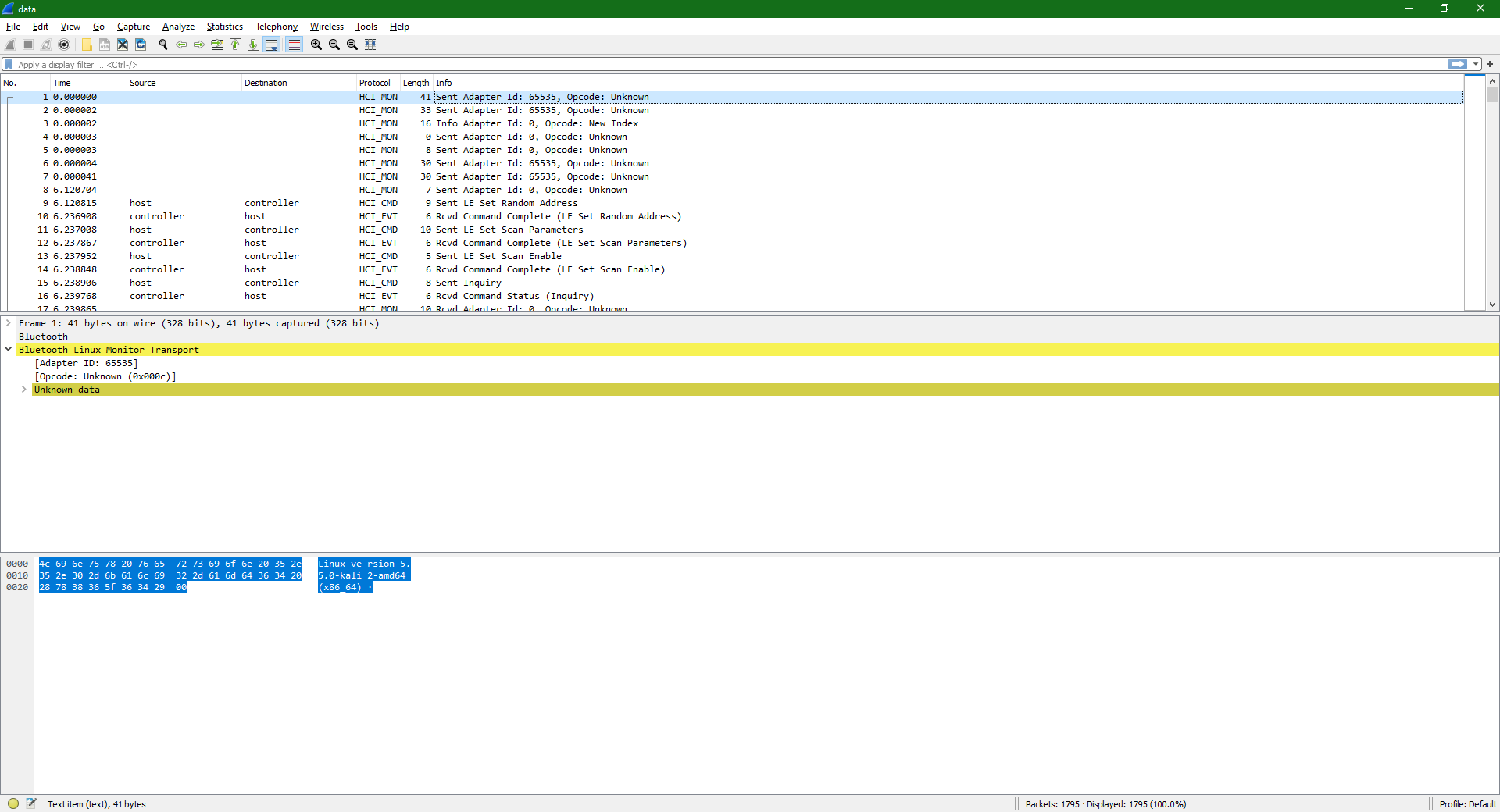

Attached was a Bluetooth HCI log in btsnoop format. I was initially unsure what to do with it, but with Still’s advice, I loaded it into Wireshark.

Inspecting the log revealed it was taken by snooping on nearby Bluetooth traffic, using Linux version 5.5.0-kali2-amd64 (x86_64), and Bluetooth subsystem version 2.22. Device was attached via hci0, the supporting daemon was bluetoothd, and the snooper was btmon. The target device identified itself as G613. A quick conversation with Still and some Google let me identify it as a Logitech™ G613 Wireless Mechanical Keyboard. Fancy stuff.

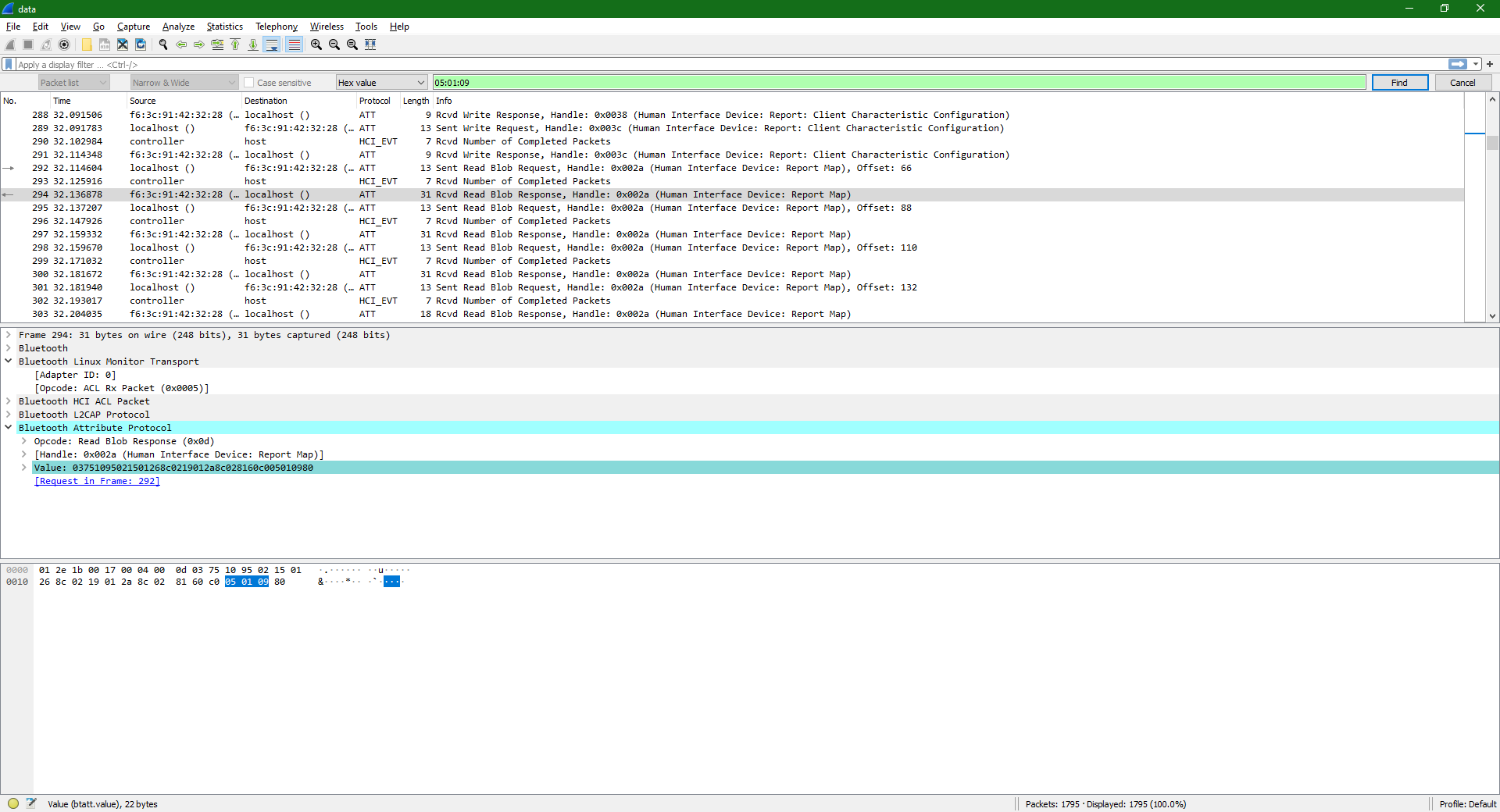

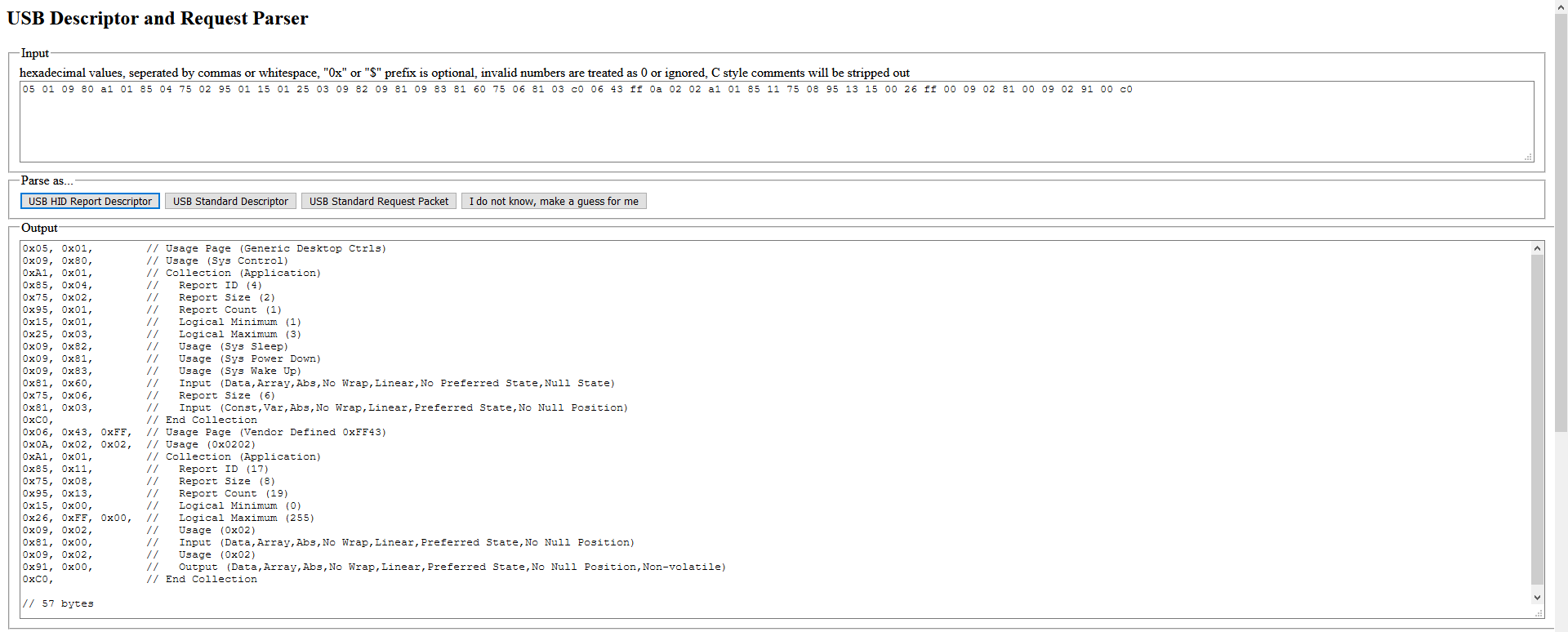

All this tells me is that I’m looking for information on how do Bluetooth keyboards talk to the target computers. The answer? HID over Bluetooth. Reading the HID specification, I find out that one of the first things a device has to do after it’s initialized is presenting itself, and describing its payloads. Googling around led me to a StackOverflow thread, where a similar problem is described. From this thread I found some important pieces of information, HID descriptors, also called Report Maps in HID terminology, tend to begin with 0x05 0x01 0x09 and tend to end with 0xc0. I searched for a relevant byte sequence in Wireshark.

The descriptor was fragmented due to Bluetooth Low Emission MTUs, so I had to reconstruct it. Using Google, I also found a HID payload decoder. I punched the reconstructed packet into the website, and let it decode it. The result was less than helpful. It looked like the keyboard description was omitted or stripped from the log.

The descriptors found in the log are for system control and vendor-specific applications, neither of which is keyboard. I decided to scroll a little in Wireshark, and reached a block of HID Reports.

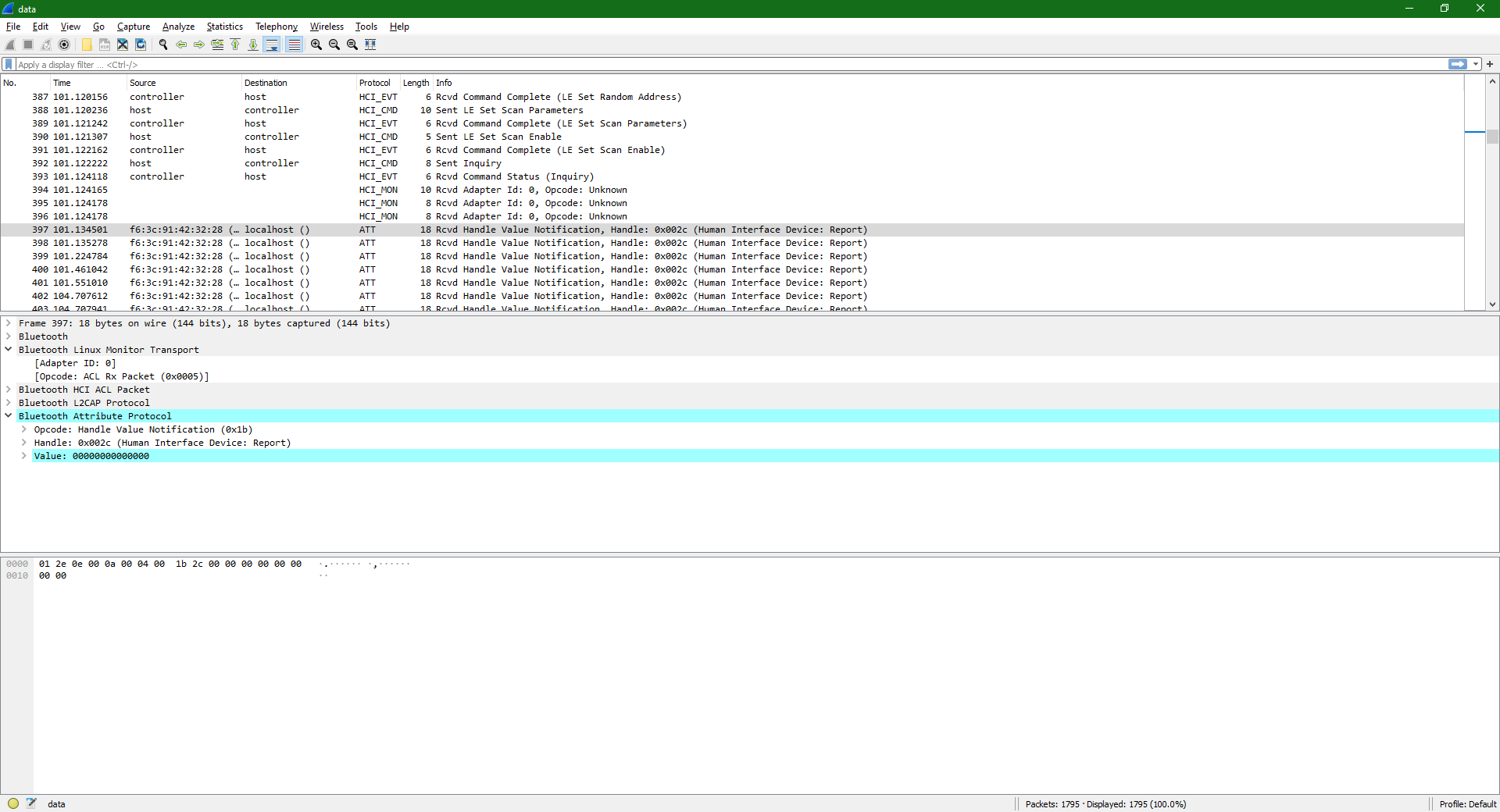

Per HID specification, a keystroke is sent as a report, so I decided to check out a couple of them to see which bytes were changing. The changing bytes would then have to be keystrokes. USB Consortium HID Usage Tables, specifically pages 53-55, have proven to be an invaluable resource in decoding the data stream. I picked some reports at random, and started taking notes.

Notice how the second byte of each payload changes. I noted down consecutive non-zero values: 0f 28 28 17 15 1c. Using the document mentioned earlier, I translated these bytes to i \n \n try. That looks like words! I now had a potential solution. All I needed to do was to filter out the noise, and export this to something I could filter with Python.

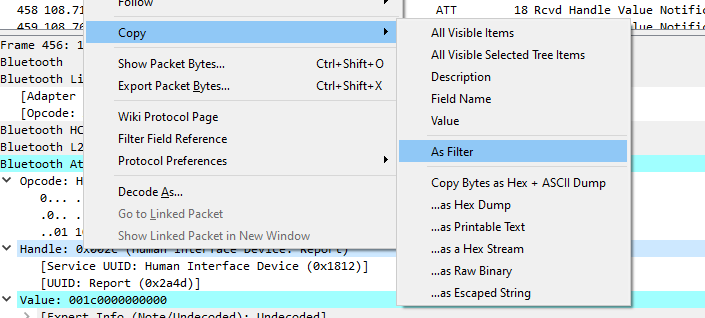

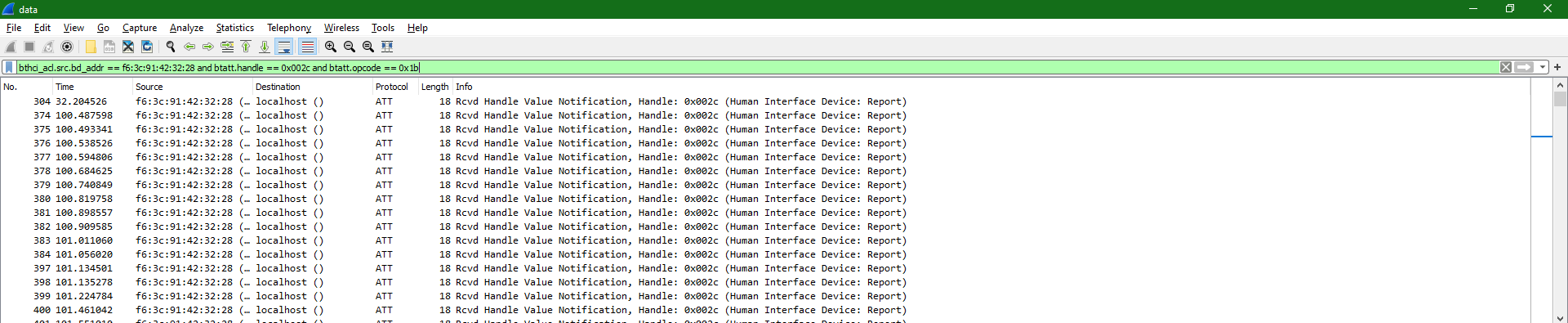

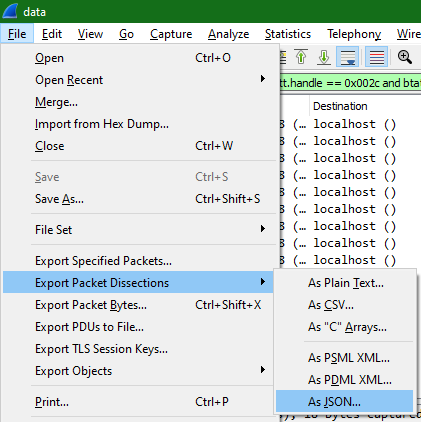

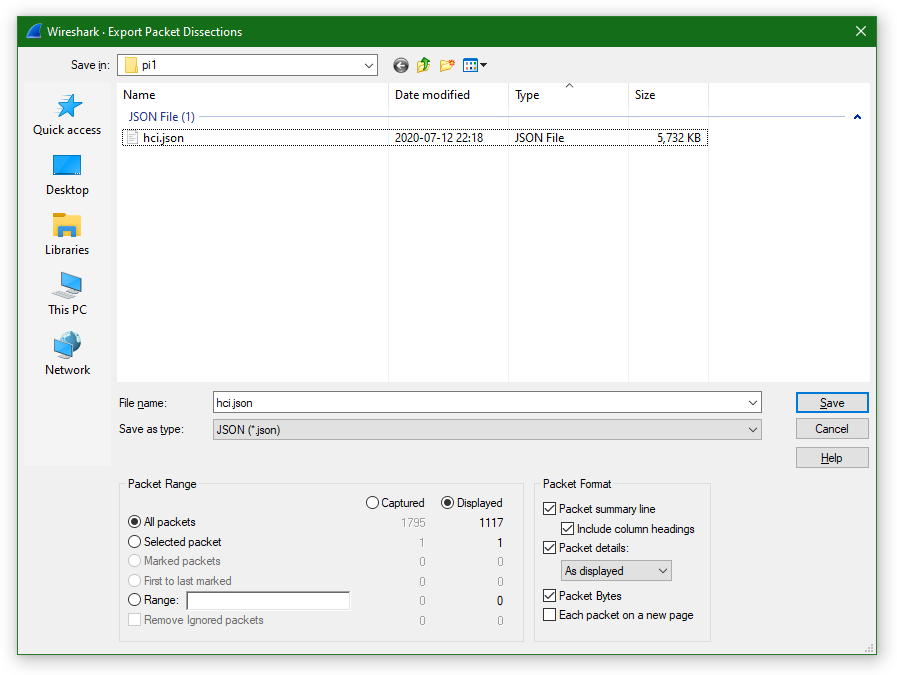

By using the Copy As Filter function in Wireshark, I created the following filter: bthci_acl.src.bd_addr == f6:3c:91:42:32:28 and btatt.handle == 0x002c and btatt.opcode == 0x1b.

All that’s left now is exporting them. Wireshark supports exporting packets as JSON, which I used to export the filtered packets. I checked to export packet bytes as well, just in case.

So now I have a >5MiB JSON file with an array of JSON packets in it. Each packet was a huge JSON object, but I only needed one part of it.

{

"_index": "packets-2020-06-27",

"_type": "doc",

"_score": null,

"_source": {

"layers": {

"frame_raw": [

"012e0e000a0004001b2c0000000000000000",

0,

18,

0,

1

],

"frame": {

"frame.encap_type": "159",

"frame.time": "Jun 27, 2020 23:49:04.697555000 Central European Daylight Time",

"frame.offset_shift": "0.000000000",

"frame.time_epoch": "1593294544.697555000",

"frame.time_delta": "0.000491000",

"frame.time_delta_displayed": "0.000000000",

"frame.time_relative": "32.204526000",

"frame.number": "304",

"frame.len": "18",

"frame.cap_len": "18",

"frame.marked": "0",

"frame.ignored": "0",

"frame.protocols": "bluetooth:hci_mon:bthci_acl:btl2cap:btatt"

},

"bluetooth_raw": [

"012e0e000a0004001b2c0000000000000000",

0,

18,

0,

1

],

"bluetooth": {

"bluetooth.addr": "f6:3c:91:42:32:28",

"bluetooth.src": "f6:3c:91:42:32:28",

"bluetooth.addr": "00:00:00:00:00:00",

"bluetooth.dst": "00:00:00:00:00:00"

},

"hci_mon_raw": [

"012e0e000a0004001b2c0000000000000000",

0,

18,

0,

1

],

"hci_mon": {

"hci_mon.adapter_id": "0",

"hci_mon.opcode": "5"

},

"bthci_acl_raw": [

"012e0e000a0004001b2c0000000000000000",

0,

18,

0,

1

],

"bthci_acl": {

"bthci_acl.chandle_raw": [

"E01",

0,

2,

4095,

5

],

"bthci_acl.chandle": "0x00000e01",

"bthci_acl.pb_flag_raw": [

"2",

0,

2,

12288,

5

],

"bthci_acl.pb_flag": "2",

"bthci_acl.bc_flag_raw": [

"0",

0,

2,

49152,

5

],

"bthci_acl.bc_flag": "0",

"bthci_acl.length_raw": [

"0e00",

2,

2,

0,

5

],

"bthci_acl.length": "14",

"bthci_acl.data_raw": [

"0a0004001b2c0000000000000000",

4,

14,

0,

0

],

"bthci_acl.data": "",

"bthci_acl.connect_in": "69",

"bthci_acl.src.bd_addr": "f6:3c:91:42:32:28",

"bthci_acl.src.name": "G613",

"bthci_acl.src.role": "0",

"bthci_acl.dst.bd_addr": "00:00:00:00:00:00",

"bthci_acl.dst.name": "",

"bthci_acl.dst.role": "0",

"bthci_acl.mode": "-1"

},

"btl2cap_raw": [

"0a0004001b2c0000000000000000",

4,

14,

0,

1

],

"btl2cap": {

"btl2cap.length_raw": [

"0a00",

4,

2,

0,

5

],

"btl2cap.length": "10",

"btl2cap.cid_raw": [

"0400",

6,

2,

0,

5

],

"btl2cap.cid": "4"

},

"btatt_raw": [

"1b2c0000000000000000",

8,

10,

0,

1

],

"btatt": {

"btatt.opcode_raw": [

"1b",

8,

1,

0,

4

],

"btatt.opcode": "0x0000001b",

"btatt.opcode_tree": {

"btatt.opcode.authentication_signature_raw": [

"0",

8,

1,

128,

2

],

"btatt.opcode.authentication_signature": "0",

"btatt.opcode.command_raw": [

"0",

8,

1,

64,

2

],

"btatt.opcode.command": "0",

"btatt.opcode.method_raw": [

"1B",

8,

1,

63,

4

],

"btatt.opcode.method": "0x0000001b"

},

"btatt.handle_raw": [

"2c00",

9,

2,

0,

5

],

"btatt.handle": "0x0000002c",

"btatt.handle_tree": {

"btatt.service_uuid16": "6162",

"btatt.uuid16": "10829"

},

"btatt.value_raw": [

"00000000000000",

11,

7,

0,

30

],

"btatt.value": "00:00:00:00:00:00:00",

"btatt.value_tree": {

"_ws.expert": {

"btatt.undecoded": "",

"_ws.expert.message": "Undecoded",

"_ws.expert.severity": "4194304",

"_ws.expert.group": "83886080"

}

}

}

}

}

}

My desired data was under _source / layers / btatt / btatt.value_raw / [0], and the characters that interested me were characters 2-6. Next step was to filter the data. I wrote a python script to tell me which keystrokes from the document I needed, and, while at it, filter out all the unnecessary data from it.

from json import load, dump

with open("hci.json", "r") as f:

t = load(f)

t1 = [x["_source"]["layers"]["btatt"]["btatt.value_raw"][0][2:6] for x in t]

t2 = [x for x in t1 if x[0:2] != "00"]

t3 = [(x[0:2], x[2:4]) for x in t2]

with open("hci_filtered.json", "w") as f:

dump(t3, f)

print("Unique keystrokes:", sorted(set(x for x, y in t3)))

This gave me the list I needed:

['04', '05', '06', '07', '08', '09', '0a', '0b', '0c', '0d', '0e', '0f', '10', '11', '12', '13', '15', '16', '17', '18', '19', '1a', '1b', '1c', '1f', '20', '22', '23', '24', '25', '26', '27', '28', '2a', '2c', '34', '36', '37', '38']

Going back to the document, I found what I needed. Range 04..1d mapped to 'a'..'z', 1e..26 mapped to '1'..'9', 27 mapped to '0', 28 was '\n', 2a was '\b', 2c was ' ', 34 was '"' or '\'' (I opted to use quotes), 36 was ',' or '<' (I opted to use comma), 37 was '.' or '>' (I opted to use full stop), and 38 was '/' or '?' (I opted to use question mark).

With that, I had to build a required keymap.

keymap = {}

# Letters: 04..1d

for x in range(26): # There are 26 latin letters

kidx = hex(x + 4)[2:].rjust(2, "0") # Shifts by 4 (lower boundary is 04), strips 0x prefix, and pads with leading 0s until length is 2: 0 -> 04, 12 -> 0a, etc

kchr = chr(ord("a") + x) # Character

keymap[kidx] = kchr

# Numbers 1-9: 1e..26

for x in range(1, 10):

kidx = hex(0x1d + x)[2:]

kchr = str(x)

keymap[kidx] = kchr

# Number 0: 27

keymap['27'] = '0'

# Other characters

keymap['28'] = '\n'

keymap['2a'] = '\b'

keymap['2c'] = ' '

keymap['34'] = '"'

keymap['36'] = ','

keymap['37'] = '.'

keymap['38'] = '?'

# Print out

print(keymap)

I verified the keymap quickly using a script.

from json import load

keymap = {'04': 'a', '05': 'b', '06': 'c', '07': 'd', '08': 'e', '09': 'f', '0a': 'g', '0b': 'h', '0c': 'i', '0d': 'j', '0e': 'k', '0f': 'l', '10': 'm', '11': 'n', '12': 'o', '13': 'p', '14': 'q', '15': 'r', '16': 's', '17': 't', '18': 'u', '19': 'v', '1a': 'w', '1b': 'x', '1c': 'y', '1d': 'z', '1e': '1', '1f': '2', '20': '3', '21': '4', '22': '5', '23': '6', '24': '7', '25': '8', '26': '9', '27': '0', '28': '\n', '2a': '\x08', '2c': ' ', '34': '"', '36': ',', '37': '.', '38': '?'}

with open("hci_filtered.json", "r") as f:

t = set(x[0] for x in load(f))

u = keymap.keys()

print("Missing definitions:", sorted(t.difference(u)))

No missing keys, great. Now I could start translating. A thing of note at this stage: every key is 1 byte, yet I exported 2 bytes for each report. This is because I noticed that some keystrokes are sent several times, with the second byte being non-zero. I don’t know what it means, however as this effectively duplicates letters, I used it to discard duplicated or other invalid keystrokes. So to translate the stream, let’s feed it to a python script.

from json import load

keymap = {'04': 'a', '05': 'b', '06': 'c', '07': 'd', '08': 'e', '09': 'f', '0a': 'g', '0b': 'h', '0c': 'i', '0d': 'j', '0e': 'k', '0f': 'l', '10': 'm', '11': 'n', '12': 'o', '13': 'p', '14': 'q', '15': 'r', '16': 's', '17': 't', '18': 'u', '19': 'v', '1a': 'w', '1b': 'x', '1c': 'y', '1d': 'z', '1e': '1', '1f': '2', '20': '3', '21': '4', '22': '5', '23': '6', '24': '7', '25': '8', '26': '9', '27': '0', '28': '\n', '2a': '\x08', '2c': ' ', '34': '"', '36': ',', '37': '.', '38': '?'}

with open("hci_filtered.json", "r") as f:

print(''.join(keymap[x[0]] if x[1] == "00" else "" for x in load(f)))

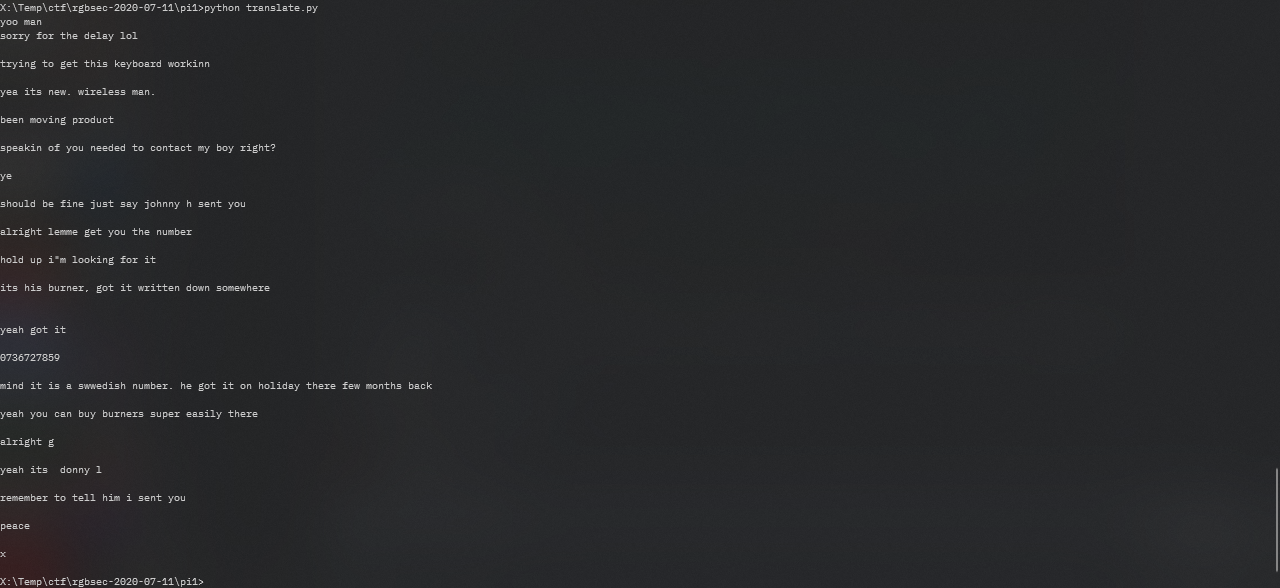

With that, I obtained the required information to construct the flag.

yoo man

sorry for the delay lol

trying to get this keyboard workinn

yea its new. wireless man.

been moving product

speakin of you needed to contact my boy right?

ye

should be fine just say johnny h sent you

alright lemme get you the number

hold up i"m looking for it

its his burner, got it written down somewhere

yeah got it

0736727859

mind it is a swwedish number. he got it on holiday there few months back

yeah you can buy burners super easily there

alright g

yeah its donny l

remember to tell him i sent you

peace

x

The 2 pieces of information pertaining to the flag are the phone number from the transcript, 0736727859, as well as the information that it’s a Swedish number, which means the dialing code is +46. By stripping the leading 0, and prepending the dialing code, I obtained the flag.

Flag:

rgbCTF{+46736727859}

Misc

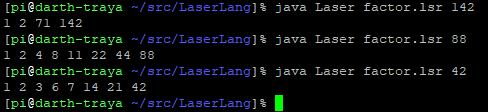

Laser 1 - Factoring (480 points)

Challenge description

https://github.com/Quintec/LaserLang Do you like lasers? I like lasers! Here's a warmup: create a program that factors the one number given as input. Output factors on one line in ascending order (or just leave them on the stack, as Laser has implicit output) Example Input: 42 Output: 1 2 3 6 7 14 21 42

We were also given an address to connect to using netcat. When connected, we’d input our code, which would then get tested against several cases. If all tests passed, the flag would be revealed. The GitHub link leads to a git repository, which hosts an interpreter for an esoteric language called Laser. An excerpt from the README paints it as an interesting challenge.

Like many 2-D languages, Laser has an instruction pointer that executes the one character instructions it encounters. The instruction pointer starts at the top left and initially points right. The pointer can wrap around the program and termination only occurs on error or the termination character #. The memory structure is a list of stacks. There are only two types in Laser: String and Number. Numbers are java Longs.

This means I will have to think differently than in all the other cases, however this is a rather simple problem. My implementation was more or less a translation of a simple C factoring program to this language, adjusted for its constraints.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

int i;

scanf("%d", &i);

for (int j = i; j > 0; --j)

if (i % j == 0)

printf("%d ", i);

return 0;

}

This implementation, when translated to Laser, looks like this:

UirrrrsUrD>⌜%uruu⌜\

U pp

P UU

P wp

D

# w

U

v/

(

r

r

w

D

\ <

The program uses the initial (bottom) stack as the result stack. It’s implicitly printed out when the program finishes its execution. The whole code works as follows:

- Create a new stack and set it as active (move from stack 0 to stack 1)

- Take first input arguments and push it on top of current stack (in the C implementation that’s

i) - Make 4 additional copies of that value

- Shift one copy to a new stack above the current one

- Set the new stack as active (move from stack 1 to stack 2)

- Make a copy of its only value (the input number)

- Set the stack below as active (move from stack 2 to stack 1)

- Set the execution direction to right.

- If the top value on the current stack (in the C implementation, that’s

j) is equal to 0, change the direction of the instruction pointer to start moving down, otherwise keep it moving left- If the direction was changed, set the stack above the current one as active (move from stack 1 to stack 2)

- Pop currently-active stack, then the next active stacks (this destroys stacks 2 and 1)

- Finish execution of the program

- If the execution direction was not changed, perform modulo of the 2nd top element by the 1st top element, and store the result on the stack

- Rotate the stack “up” (meaning the bottom element becomes the top)

- Duplicate the now-top element

- Rotate the stack “up” 2 times again

- If the now-top element (modulo result) is equal to 0, change direction to down, otherwise keep it as left

- The false branch is then also redirected down, such that it runs in parallel to the true branch

- Both branches pop the modulo result

- Both branches set the stack above as active (move from stack 1 to stack 2)

- Operation here depends on the modulo result

- False branch pops the top item from the current stack

- True branch moves the top item down one stack (from stack 2 to stack 1)

- True branch changes active stack to the stack below (from stack 2 to stack 1)

- True branch moves top item from the active stack down one stack (from stack 1 to stack 0) - effectively pushing it on top of the result stack

- True branch sets the stack above as active (from stack 1 to stack 2)

- Both branches are merged at this point

- The top value on the stack (

jfrom C implementation) is decremented by 1 - It’s then duplicated twice

- Next, the top copy is shifted down one stack (from stack 2 to stack 1)

- The stack below is then set as active (from stack 2 to stack 1)

- The program then redirects the execution so that it returns to point 9

When the program finishes execution, the result stack is typed out, resulting in the factors of given number being typed out in ascending order.

In the program above, you should notice that the program termination is separated by a blank space from popping the 2 stacks. That’s because initially there was a “print current stack” instruction in there, but due to a bug, the test cases didn’t accept its output. As the language types the current stack out implicitly when execution finishes, it’s not necessary anyway. After the code, I also put in 3 newlines, to make the remote server recognize the end of code properly.

The testing program, however, had an interesting bug, where using the stack print instruction caused the output to be echoed back to sender, which allowed for limited debugging of inputted code.

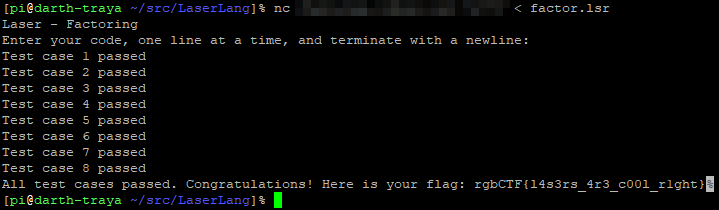

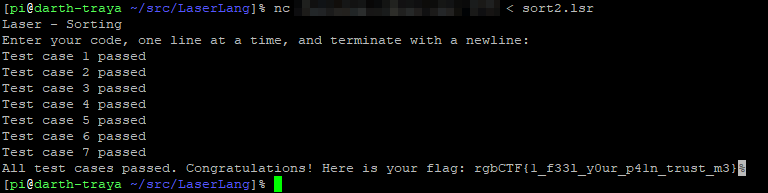

After my testing concluded, I sent the program for testing. Test case 8 took a little while, probably because it was a large number, but once I passed, I got the flag.

Flag:

rgbCTF{l4s3rs_4r3_c00l_r1ght}

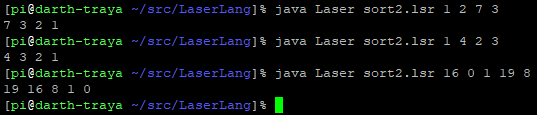

Laser 2 - Sorting (491 points)

Challenge description

https://github.com/Quintec/LaserLang Here's a harder Laser challenge. Given an input stack of numbers, sort them in descending order. Input: 1 2 7 3 down the rockefeller street Output: 7 3 2 1

Like with previous challenge, we were also given an address to connect to using netcat, in order to input our code.

This challenge was much more difficult than previous one, as it basically required swapping elements, something Laser lacks built-in facilities for. The algorithm I devised worked more or less like so:

- Push all inputs onto one stack

- Create another stack for sorted output

- Pick the smallest value from input stack, push it on the sorted stack, pop it from input stack

- If any numbers are remaining on the input stack, go to point 3

- Print out the output

If implemented in C++, the program would look more or less like this:

#include <algorithm>

#include <string>

#include <stringstream>

#include <deque>

#include <iostream>

int main(int argc, char*[] argv)

{

std::deque<int> input, sorted;

std::stringstream ss;

int t;

for (int i = 1; i < argc; i++)

{

ss << argv[i];

ss >> t;

input.push_back(t);

}

while (!input.empty())

{

auto minel = min_element(input.begin(), input.end());

sorted.push_back(*minel);

input.erase(minel);

}

while (!sorted.empty())

std::cout << sorted.pop_back();

return 0;

}

In Laser, the implementation looks like this:

v vdD r< <

p U

\UI>sUrDc)w>D(⌝UrsUg⌟pwDdsu^

p vDpUUp<

" c

= ⌞Pc(⌝p#

^" p< >p#

This is a lot to unwrap, so I’ll do it in 2 stages - a general overview of the program’s operation, and a detailed breakdown.

The program uses 3 stacks - the top one is the sorted stack, middle one is the input stack, and the bottom one is a counter stack (used to count loop iterations). The program works by essentially putting the current input stack size in the counter stack, top value from the input stack at the output stack, then it compares the top input value with top sorted value. If the input one is smaller, they are swapped. The value on the counter stack is then decremented. The compare-swap operation is repeated as many times, as there are elements in the input stack (including the shifted one). After one such cycle of operations, the sorted stack now has the smallest value from the input stack pushed to the top.

For inputs like 1 4 2 3, the stacks would look like so after every cycle

cycle = 0

input [1 4 2 3]

sorted []

cycle = 1

input [4 2 3]

sorted [1]

cycle = 2

input [4 3]

sorted [2 1]

cycle = 3

input [4]

sorted [3 2 1]

cycle = 4

input []

sorted [4 3 2 1]

The sorted stack is set as active at the end of the program, which causes it to be printed out.

In greater detail, the program works as follows:

- Reflect the execution such that it occurs 2 lines down

- Initialize a new stack above the current one (move from 0 to 1)

- Push all input arguments onto current stack

- Set execution direction to right

- Create a new stack above the current one, and push the current top value on the stack (first input) one stack up (from 1 to 2)

- Set the stack above (sorted) as the active one (move from 1 to 2)

- Duplicate the value on top of current stack

- Move down 1 stack (from 2 to 1 - input)

- Count the elements on the current stack and push the count on top

- Increment the top value (so that for n elements the compare-swap cycle is done

ntimes, notn-1times) - Move the top value (count) down 1 stack (from 1 to 0 - counter)

- Set execution direction to right

- Move down 1 stack (from 1 to 0 - counter)

- Decrements the top value by 1

- If the current top value (remaining compare-swap iteration count) is 0, change execution direction to down (jump to point 36), otherwise keep executing to the left.

- Move up 1 stack (from 0 to 1 - input)

- Duplicate the top value (next processed input)

- Move the new value up 1 stack (from 1 to 2 - sorted)

- Set the stack above as active (from 1 to 2 - sorted)

- Check if the 2nd top element is greater than the top element (if the currently-inspected element is smaller than already-sorted element)

- If that is not the case, change execution direction to up and pop the comparison result (then go to point 30)

- If it is, meaning we have to swap the two values, pop the comparison result

- Move the top element down one stack (from 2 to 1 - input)

- Set the stack below as active (from 2 to 1 - input)

- Rotate the stack down (place the top value at the bottom)

- Move the top value up one stack (from 1 to 2 - sorted) - the elements are now swapped

- Set execution direction to up

- Set the stack above as active (from 1 to 2 - sorted)

- Set the execution direction to left

- Set the execution direction to left

- Duplicate the top value

- Set the stack below as active (from 2 to 1 - input)

- Rotate the stack down (place the top element at the bottom)

- Set the execution direction to down then left

- Go to point 12

- Set the execution direction to left

- Pop the top value (counter) e from the current stack

- Set the stack 2 above as the current (from 0 to 2 - sorted)

- Pop the top value (duplicate of the just sorted value)

- Set the stack below as the active one (from 2 to 1)

- Set execution direction to down

- Count the input elements, if they’re 0, change execution direction to right (jump to point 47), otherwise keep going down

- Change execution direction to left and pop the top item (input count)

- Push = string on the stack, while changing execution direction to up

- Pop the top item (for debugging, this can be replaced with

o, which prints the top stack item; the character is used to separate compare-swap cycles) - Go to point 4

- Pop the entire stack (input), which sets the current stack to sorted

- Count the elements (this is used for debugging) and decrement the count

- In either case, pop the count, and stop the execution

The output is sorted in descending order.

Using the bug I described above, I used to debug this program, as I had a glitch initially, where for some inputs the program didn’t sort properly. It got stuck on case 2, so I made it print the stack out when there was more than 1 input. This was removed for the final version. Again, at the end of the program, there were 3 empty lines.

After my testing concluded, I sent the program for testing. After ironing out the kinks, all tests passed, and I got the flag.

Flag:

rgbCTF{1_f33l_y0ur_p41n_trust_m3}

Web

Tic-Tac-Toe (50 points)

Challenge description

Hello there, I invite you to one of the largest online global events in history ... the Tic Tac Toe World Championships!

We were also given a link to the application we were meant to exploit.

The challenge is a classic - a tic-tac-toe game. In order to obtain the flag, all you had to do was defeat the AI. I should mention that when I solved it, the challenge was broken, and any win counted as a loss, which got fixed after I solved the challenge. It did not, however, stop me.

I decided that the best place to start was the JavaScript code powering the application. Unfortunately, it was heavily obfuscated, so analysis wasn’t easy. Using Firefox dev tools’ pretty print feature made it somewhat more readable, but it still couldn’t be analyzed in a nice manner.

While analyzing, however, I noticed a certain variable, which in my instance was called _0x517520, defined as const. It was an array of three-element arrays, and since it was a const, I could not change its value directly, but I knew I could change its contents. With a bit of inspect element and deduction, I reached the conclusion that it held the winning combinations. My first thought was to try and remove some of them, but that only caused the application to crash.

My next idea was inspired by Star Trek, specifically James T. Kirk’s approach to an unwinnable scenario simulation - I decided to change win conditions, and see what comes out.

I fired up the console, and punched the following snippet in:

for (var i = 0; i < _0x517520.length; i++) for (var j = 0; j < 3; j++) _0x517520[i][j] = 0;

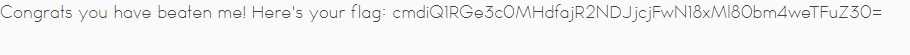

Then I placed my mark in the top-left corner. Sure enough, the application spilled out a base64-encoded string: cmdiQ1RGe2g0aDRfajR2NDJjcjFwN19ldjNuNzJfQVIzX2MwMEx9.

After decoding it, I obtained the flag. Judging by its contents, I am pretty sure this was not the intended way of solving this challenge.

Flag:

rgbCTF{h4h4_j4v42cr1p7_ev3n72_AR3_c00L}

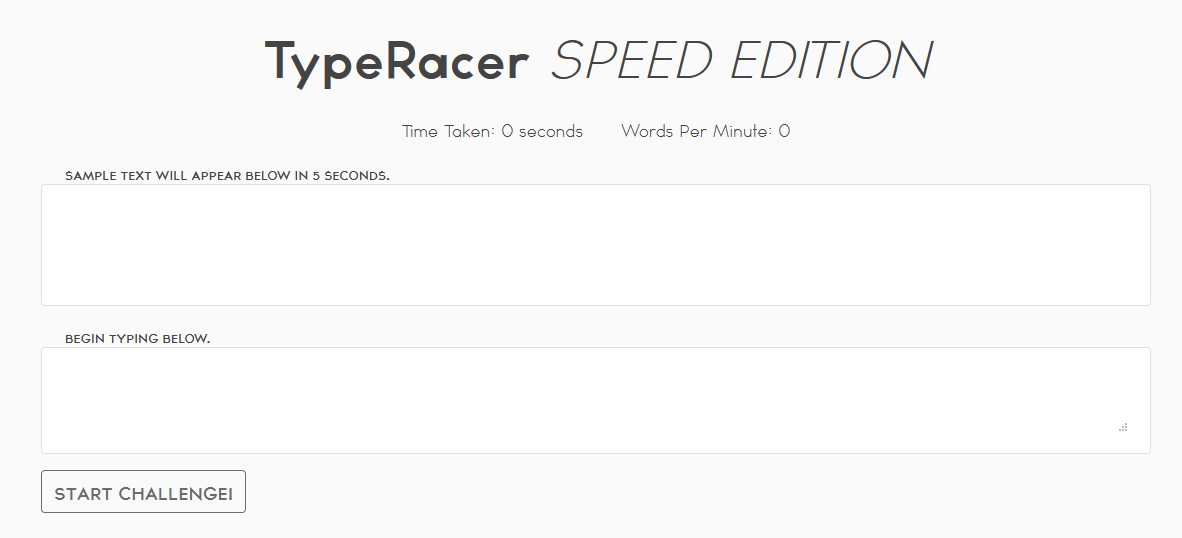

Typeracer (119 points)

Challenge description

I AM SPEED! Beat me at TypeRacer and the flag is all yours!

We were once again given a link to an application we were meant to defeat - a typeracer clone.

The way this application worked was rather simple. You press start, wait 5 seconds, and then a list of words appears in the top box. You are meant to type them in the order you can see them. If your typing speed is above certain (very high) threshold, the flag is revealed.

I’m a relatively fast typer (around 100-120 WPM touch-typing), so I tried the classic approach first, just to get a feel for the application. Obviously, I didn’t win. But it gave me an idea - only a robot can beat a robot.

I got to work trying to automate the typing. My first thought was to create a script, which automatically starts typing, once the words appear. The DOM has a useful feature for this - MutationObservers. You can attach an observer to an element, specify what kind of changes to look for, and it will automatically fire a callback you specify once the change occurs. So begins the adventure.

// Get the field wherein the text will appear

var ttext = document.getElementsByClassName('card mt-0')[0].getElementsByClassName('card-body')[0];

// Create an observer

var obs = new MutationObserver(m => {

// Disconnect so it doesn't fire multiple times

obs.disconnect();

// Retrieve the text

var txt = ttext.textContent;

console.log(txt);

// Do work

});

obs.observe(ttext, { characterData: true, attributes: false, childList: false }); // observe text changes

But that didn’t work. A quick inspect element later, I figured out why. The text was appended as a collection of spans, so instead of watching for text changes, I had to watch for child changes.

{ characterData: false, attributes: false, childList: true }

Ok, so now I got the text (at the time it was incorrect, which I didn’t notice), I have to type it somehow. Since a typeracer is a typing speed challenge, I decided decided to look around how to simulate keyboard events using JavaScript. One Google later, I found this StackOverflow thread, and combined it with a set of setTimeout()-based delays, in order to send the characters in order. This, however, did not work! It turned out that for some reason, the application didn’t understand or purposefully rejected any keystrokes generated from within JS. I had to take another approach.

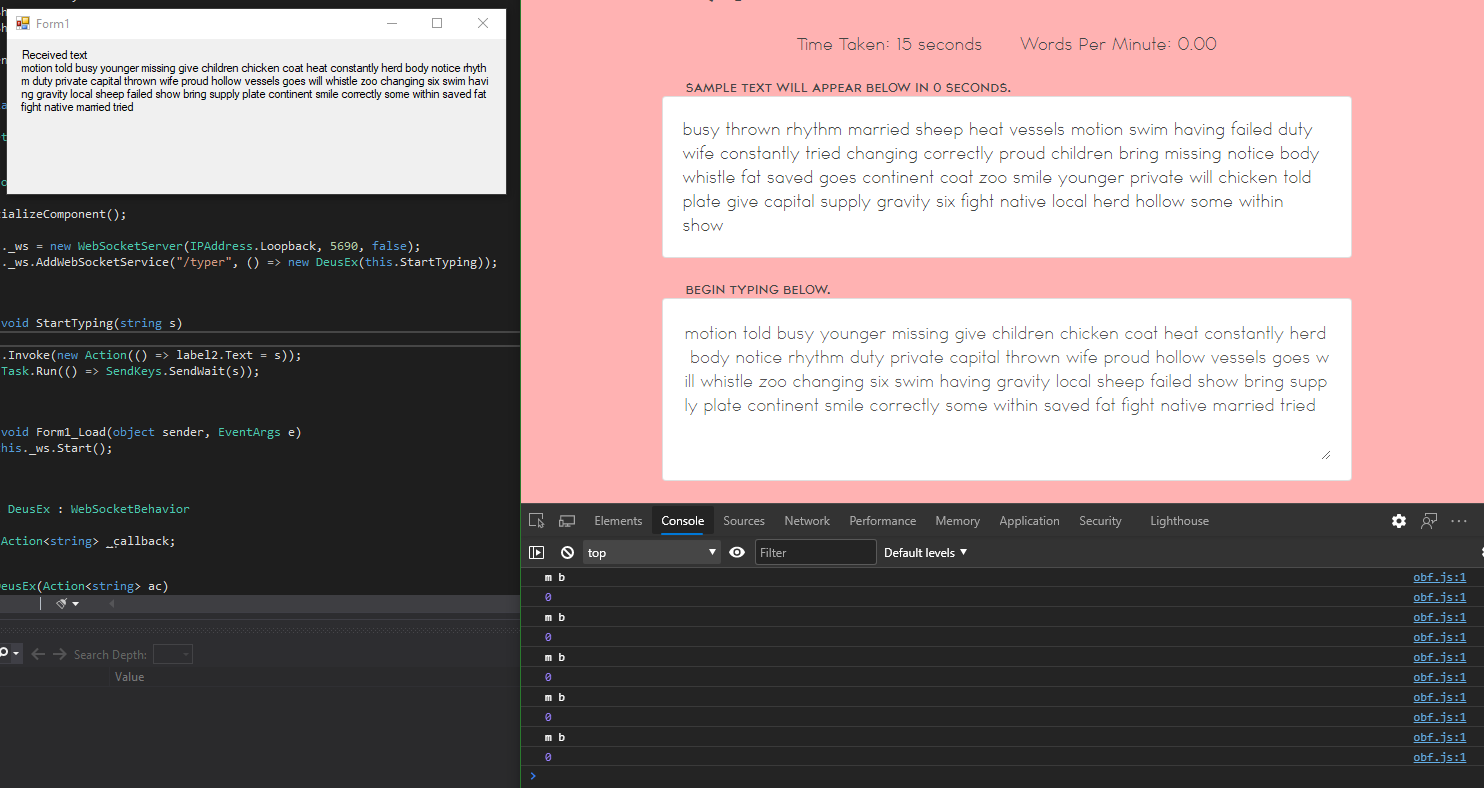

I had several options here, first one being using a web driver like Selenium. However, I didn’t want to download and install Selenium just for this challenge. I know I could achieve something similar using VBA macros in Microsoft Excel, in order to automate Internet Explorer interactions, but that seemed too crazy. Eventually it hit me, I could automate a keyboard using an external program.

In order to communicate with the program, I had to use WebSocket protocol, as that is the only protocol I can use directly in JavaScript without any weird proxies. Since C# is my primary language, I fired up Visual Studio, and created a new WindowsForms application.

In C#, there exists a class called SendKeys, which allows you to send keystrokes to other applications. For diagnostic purposes, I gave the window a label, which would print out any received text. I then added a hosted WebSocket server to the application, using WebSocketSharp library. Finally, I made the server start when the window was loaded. The whole code-behind for the application looked like this:

using System;

using System.Net;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using System.Windows.Forms;

using WebSocketSharp;

using WebSocketSharp.Server;

namespace AutoSendKeys

{

public partial class Form1 : Form

{

WebSocketServer _ws;

public Form1()

{

InitializeComponent();

this._ws = new WebSocketServer(IPAddress.Loopback, 5690, false);

this._ws.AddWebSocketService("/typer", () => new DeusEx(this.StartTyping));

}

private void StartTyping(string s)

{

this.Invoke(new Action(() => label2.Text = s));

_ = Task.Run(() => SendKeys.SendWait(s));

}

private void Form1_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

=> this._ws.Start();

}

public class DeusEx : WebSocketBehavior

{

private Action<string> _callback;

public DeusEx(Action<string> ac)

=> this._callback = ac;

protected override void OnMessage(MessageEventArgs e)

=> this._callback(e.Data);

}

}

I then had to make the JavaScript code send the string to my application. I added a WebSocket connection to the mutation observer.

var ttext = document.getElementsByClassName('card mt-0')[0].getElementsByClassName('card-body')[0];

var obs = new MutationObserver(m => {

obs.disconnect();

var txt = ttext.textContent;

console.log(txt);

// Connect to our SendKeys app and tell it to type the string

var ws = new WebSocket("ws://localhost:5690/typer");

ws.addEventListener("open", e => { ws.send(txt); ws.close(); });

});

obs.observe(ttext, { characterData: false, attributes: false, childList: true });

I started my typer application, ran the snippet on the typeracer application, pressed start, and waited. When the typing began, it was all wrong.

Cursory analysis revealed the words were not in the correct order. But how could that be? I decided to inspect the upper box again, and found a curiosity. The elements were placed out-of-order, and for display purposes, were reordered using a CSS order rule. I had to modify the text retrieval part of my script to account for that.

var ttext = document.getElementsByClassName('card mt-0')[0].getElementsByClassName('card-body')[0];

var obs = new MutationObserver(m => {

obs.disconnect();

// Get the child spans and order them

var els = [].slice.call(ttext.getElementsByTagName('span'));

var txt = els.sort((a, b) => a.style.order - b.style.order).map(x => x.textContent.trim()).join(" ");

console.log(txt);

var ws = new WebSocket("ws://localhost:5690/typer");

ws.addEventListener("open", e => { ws.send(txt); ws.close(); });

});

obs.observe(ttext, { characterData: false, attributes: false, childList: true });

I reran the snippet, this time with a much better result. The application spilled out a base64-encoded string: cmdiQ1RGe3c0MHdfajR2NDJjcjFwN18xMl80bm4weTFuZ30=.

Decoding the string yielded the flag. End of story

Flag:

rgbCTF{w40w_j4v42cr1p7_12_4nn0y1ng}

Bonus

I mentioned that one way of beating this challenge is automating Internet Explorer via VBA Macros in Excel (which is a truly wonderful tool). If you read this far, you’re probably interested in learning how to do this. As a starting point, I recommend this article on the subject.

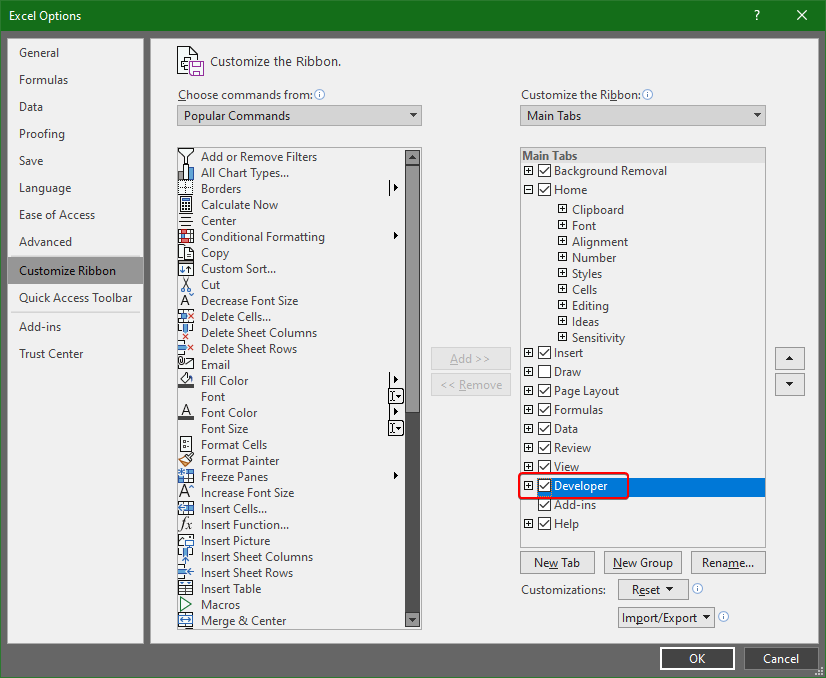

One prerequisite for this is enabling the developer tab in Excel. One can do this, by going to File > Options > Customize Ribbon, and checking Developer in the right pane.

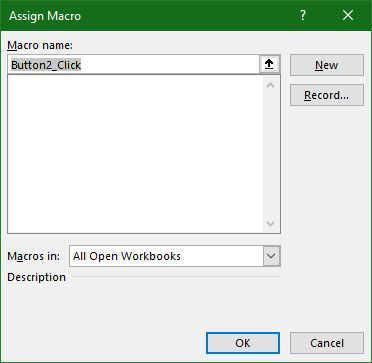

That will enable the tab, and access to Visual Basic editor. Before we do that, however, we have to insert a button that will trigger this chain of unfortunate events using the Insert dropdown. In there, select a Button under Form Controls, draw it on the workbook, and when asked about the assigned macro, press New.

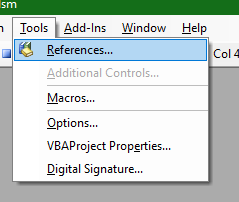

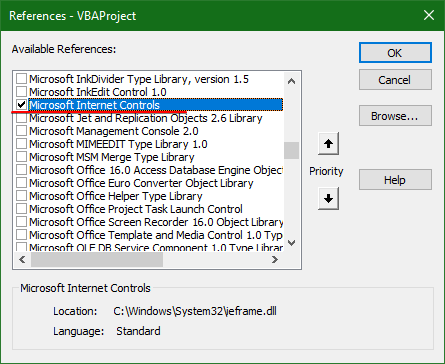

This will open the Visual Basic editor, with autogenerated method signature. Into that method, paste the following code. You need to add a COM reference to Microsoft Internet Controls, Microsoft HTML Object Library, and Microsoft XML, v6.0 using Tools > References.

Then it’s a matter of committing some crimes against humanity to get the thing working. You can find the incantation to summon dark forces below.

Public Declare PtrSafe Function SetForegroundWindow Lib "user32" (ByVal HWND As LongPtr) As LongPtr

Sub CommitTerribleSins()

' As VBA does not support inline initialization, declare variables first

Dim IE As New InternetExplorer

' Begin by creating an Internet Explorer handle and making the window visible

'Set IE = CreateObject("InternetExplorer.Application")

IE.Visible = True

IE.Navigate "http://challenge.rgbsec.xyz:8973/"

' Set IE as foreground

Dim HWND

HWND = IE.HWND

SetForegroundWindow HWND

' Wait for the page to load

' Navigation may not be instant, so first wait until ready expires, then

' wait until it's ready

Do While IE.ReadyState = 4

DoEvents

Loop

Do Until IE.ReadyState = 4

DoEvents

Loop

' I CBA to do this using events

' Add observer

IE.document.parentWindow.execScript code:="var ttext=document.getElementsByClassName('card mt-0')[0].getElementsByClassName('card-body')[0],obs=new MutationObserver(function(){obs.disconnect();var t=[].slice.call(ttext.getElementsByTagName('span')).sort(function(t,e){return t.style.order-e.style.order}).map(function(t){return t.textContent.trim()}).join(' ');console.log(t),document.location.hash=t});obs.observe(ttext,{characterData:!1,attributes:!1,childList:!0});"

' Trigger

Dim activator

Set activator = IE.document.getElementsByClassName("btn-outline-dark")

activator(0).Click

' Target

Dim target

Set target = IE.document.getElementsByTagName("textarea")(0)

' Continue doing events

Do Until InStr(IE.LocationURL, "#")

DoEvents

Loop

' Extract the fragment

Dim fragment

Dim words

fragment = IE.LocationURL

fragment = Split(fragment, "#")

fragment = fragment(1)

words = Split(fragment, " ")

' Counter

Dim counter As Integer

Dim maxcount As Integer

counter = 0

maxcount = UBound(words) - LBound(words) ' Yeah, arbitrary indexing; also don't add 1

' Set the control value

Cells(10, 3).Value = fragment

' Type it out

target.Focus

For Each word In words

If counter = maxcount Then

Application.SendKeys word, True

Else

Application.SendKeys word & " ", True

End If

counter = counter + 1

Next

' Wait for flag to appear

Cells(13, 3).Value = "Please wait..."

Application.Wait Now + TimeValue("00:00:03")

' Extract flag

Dim flag As String

flag = IE.document.body.textContent

flag = Split(flag, ":")(1)

flag = LTrim(flag)

'Cells(13, 3).Value = flag

' Decode flag

' ...using Microsoft XML

Dim objXML As New MSXML2.DOMDocument60

Dim objNode As MSXML2.IXMLDOMElement

Set objNode = objXML.createElement("b64")

objNode.DataType = "bin.base64"

objNode.Text = flag

flag = StrConv(objNode.nodeTypedValue, vbUnicode)

Set objNode = Nothing

Set objXML = Nothing

' Set flag

Cells(13, 3).Value = flag

' Close IE

IE.Visible = False

Set IE = Nothing

' You are now going straight to hell. You are also on every list imaginable. ggwp no re

End Sub

And with that, we have a fully-functional, fully-automated CTF solver, all in Microsoft Excel. Microsoft Excel can do everything. It can replace you. Do not joke about Excel. It will come for you.

The result of this unholy union can be downloaded here.

Leave a comment